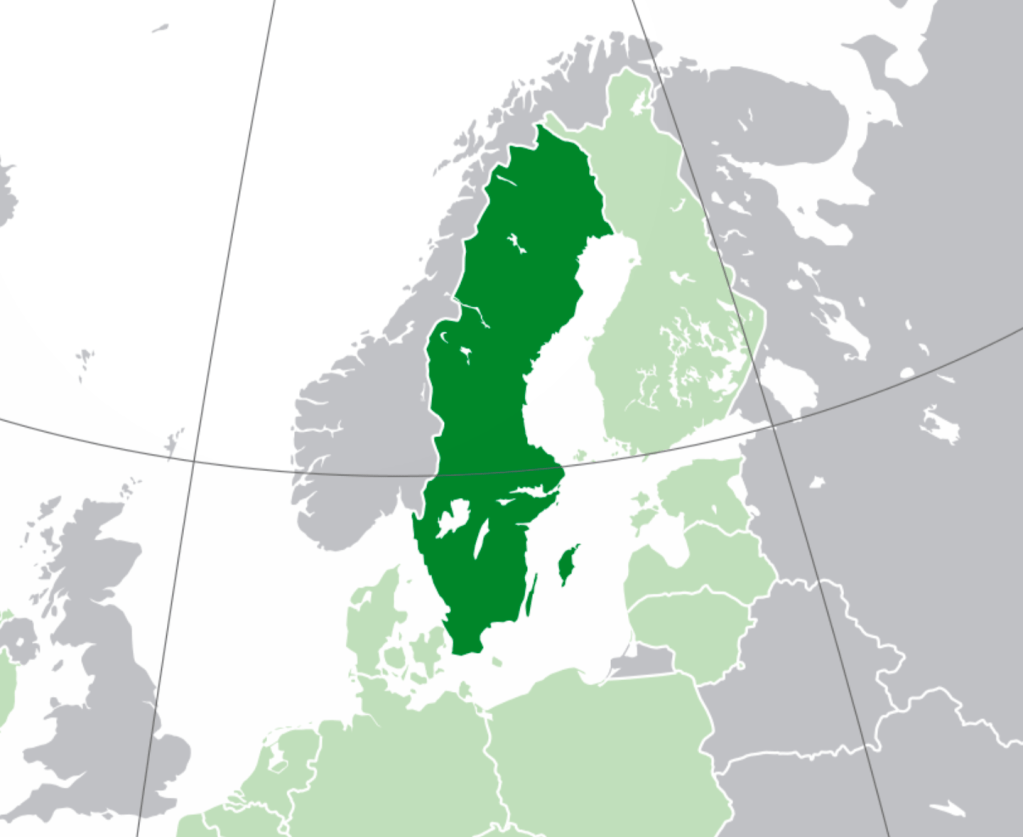

Sweden represented a bit of an unknown quantity for me. I knew Denmark had the shelters, Norway the epic mountains, but what about Sweden? In all honesty I didn’t really know much about the country at all.

They’re not short on big brand exports: IKEA, Volvo, Spotify, ABBA. But I’ve never had a clear image in my mind of the landscape, the regions, or the Swedes themselves. I’m also not sure why turnips are called swedes in some parts of Britain – turnip is one of our lexicon’s finest and should be used at every opportunity – but we digress.

A quick geography recap: Sweden sits at the heart of what this blog refers to as Scandinavia (i.e. Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Finland). It’s the biggest of these four countries, extending from well into the arctic circle down to below Copenhagen, but without getting all skinny at the top like Norway does. It also has double the population of its Nordic neighbours, but most folk live in the southern and coastal areas leaving vast swathes of sparsely populated countryside, especially in the north west.

Sadly for Swedish public finances they don’t possess a wealth of oil & gas reserves like their Norwegian neighbours, but on the plus side (for me at least) the cost of living is lower here – maybe that sharp stabbing pain whenever the price pops up at the till will subside?

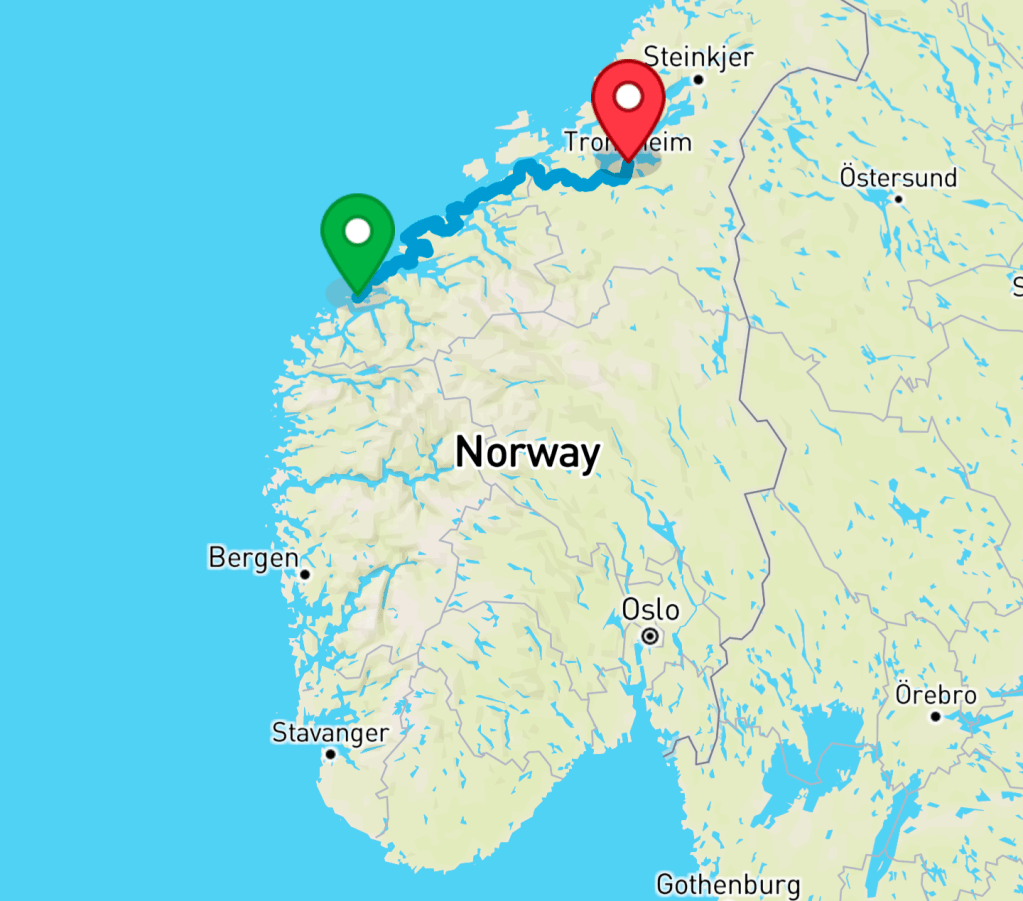

Sadly there would simply not be enough time for me to spend the best part of a month exploring Sweden as I did in Norway, so my plan was to cross the border at approximately the geographic centre then make my way east to the coast, entering through the historic province of Jämtland which once upon a time was a country of its own.

Crossing the border

My time in Trondheim was fairly short lived, where after my 4:30am bedtime it felt almost dreamlike. I rode down from the forest where I’d camped and into the city following a long gradual descent that seemed to go on and on, conscious I would later have to ride back up the hill to my out-of-town Airbnb.

I spent my limited budget of spare time to check out the impressive façade of Nidaros Cathedral (Nidaros being the old name of Trondheim), the most northern cathedral in Christendom apparently. I was a bit late to go in and see the shrine of St Olaf (the Norwegian king credited with flushing out that nasty paganism and bringing Christianity to the Scandinavia), but I would later find constant reminders that Nidaros is the endpoint for pilgrims walking the St Olavsleden trail on their way from the east coast of Sweden.

Rather than set off for Sweden straight from Trondheim I took a short train journey up to the town of Verdalsora (aka ‘Verdal’), which had a much quieter looking road over the border. I’d had visions of double-trailer logging trucks relentlessly passing by at high speed on the larger roads in Sweden, which I was keen to minimise where possible.

As it happens there’s a quarry around 10km outside of Verdal, so I had the good company of double-trailer lorries full of crushed rock for this section instead. The roads typically have a bit of space on the verge side of the white line so you have somewhere to go if it feels a bit close – and if you run out of gap then it might be time to go off road.

I met a couple of Norwegians in a layby on their way back from a shopping trip to Sweden. They’d filled the car boot with beer, pop and various other goodies that fetch an eye watering price in Norway. Part of me was pleased to hear actual Norwegians acknowledging the obscenely high prices in their country – after a while you start to wonder if this is just what things cost now? Maybe I’m just being nostalgic, like when folk tell you how cheap everything was before decimalisation, without doing the necessary conversations from imperial and adjustments for 50 years of inflation.

Eventually the farm land subsided and was replaced by hills cloaked in trees. The road was following a river that drained from the mountain range that separates Norway and Sweden, the gradients were never too severe, but I seemed to have been going slowly uphill for hours and hours which can grind you down. I tried to take inspiration from the salmon that make the same journey up the river as they migrate to their spawning ground, then remembered that they usually die shortly afterwards.

At the village of Sandvika I had a choice to make – keep going along the ‘main’ road or go for something more off the beaten track. There hadn’t been much traffic to be fair, but I still liked the idea of the minor road so I took a left and headed for the Swedish border near the Skäckerfjällen Nature Reserve.

Following the trend of recent weather the heavens opened and it began to absolutely tip it down about 5km from the border. I took shelter in what I think was someone’s driveway under a suitably bushy tree, cowering in the fetal position with my hood up. It might look slightly odd, but it’s a good way to stay dry and get some rest whilst the heaviest rain passes.

I have no idea what the other border crossings in Sweden are like, but at the one I chose the beautifully smooth Norwegian tarmac road immediately crumbles into a brown assortment of compressed mud, gravel and potholes. It had been raining so much there was a film of surface water over the mud which made the going both slippery and slow.

After 45 minutes or so of riding I became increasingly conscious of the absence of cars and houses, there wasn’t much before the border and absolutely nothing since crossing. I knew that Sweden had some proper wilderness but I didn’t expect to dive straight into it from the get go. The rain was getting heavier, and for the first time on the entire trip it felt like I was in a genuinely remote corner of Europe. It occurred to me that now would be a really bad time to break the bike and I took extra care to weave between the myriad of potholes, although if I did end up stranded at least I had plenty of food and water.

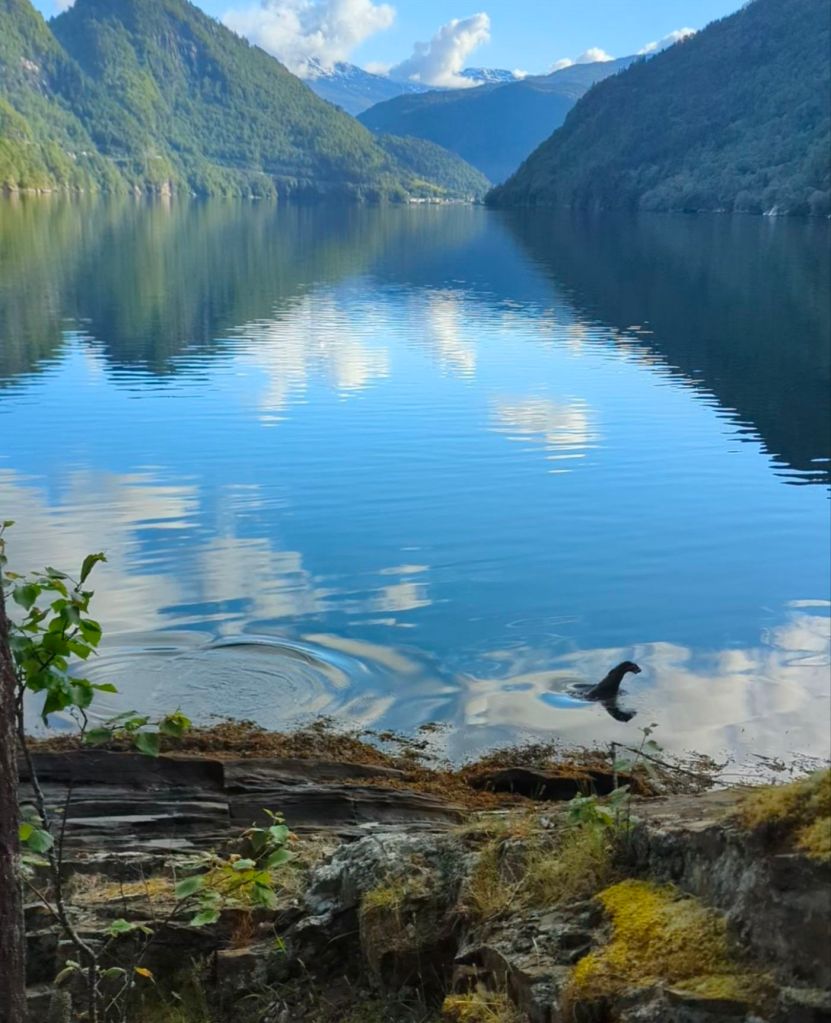

The dense spruce plantations of Norway were replaced by a much less densely packed and natural looking forest, with plenty of dead wood on the ground and silver birch mixed in with the coniferous species. The wooded areas frequently broke out into wide open spaces where the ground was covered in low lying heather and small mossy knolls. There was no shortage of water up here; the landscape was scattered with deep black pools, occasionally breaking out into vast lakes surrounded by wilderness on every side.

As I cycled along I was joined by dozens of small finches darting from the branch to branch with flashes of green and gold, whilst the larger thrushes hopped around in the grass verge looking for a meal. Norway sometimes felt a little lacking in bird life but here it was thriving.

I turned a corner and saw something large up ahead. It was a deer-like animal standing on the verge about 100m away, but it seemed to see me first and quickly extracted itself from view by disappearing into the woods. I was convinced it was a moose, and sure enough the same thing happened again 30 minutes later, but this time the animal stood its ground whilst we stared at one another for a few moments.

After a while the illusion of cycling into the last great wilderness began to fade as I was passed by the occasional car and came across houses here and there. On a sunny day it would have been incredible to find a camp spot in one of those forest clearings beside a vast lake, but I would have gotten absolutely drenched just trying to find a decent spot never mind put up the tent. I’d spotted a campsite about another hour’s cycling away in the village of Kallsedet – so with the weather getting steadily worse I shovelled down a few handfuls of dried fruit & nuts and went fully steam ahead.

Around five minutes from the campsite it began to truly hammer down, so rather than set up the tent on arrival I just took shelter on a bench under the canopy of the (closed) reception building. I’d have been happy to sit and cook my evening meal there and then, but the owner soon returned from his evening dog walk and showed me to the central heated ‘camping kitchen’. It was as basic as a kitchen can get – two hot rings and a microwave – but a stark difference to cowering for cover in the pouring rain outside.

As I cooked up some pasta I got chatting to a Belgian couple as they battled it out over a game of Scrabble (Flemish rules – less points for a J). We were the only one’s daft enough to be in a tent that evening, but at least theirs was already constructed. I considered sleeping on a bench in the laundry room, but a brief gap in the weather allowed me just enough time to get the tent up one one of the few remaining un-waterlogged patches of grass.

I would spend two nights at Kallsedet waiting for the rain to pass. It’s a great basecamp for venturing into the surrounding wilderness, as it was for the Belgian couple (they had brought a canoe and were keen bird watchers), but I was getting itchy feet and just wanted to move on.

Options Paralysis

If an organisation has a problem, and you give them a full toilet roll list of options to try and fix that problem, that’s a recipe for options paralysis. When you sit and look at a map wondering where to go next, if you have no knowledge about towns you’d like to pass through or things to see, the number of possible routes can be similarly overwhelming. I wanted to see a bit more deep countryside before getting to civilisation, so I settled on taking the back roads to the central city of Östersund, with a goal to find some well preserved rock art along the way.

It wouldn’t be the first time I would feel paralysis begin to creep in. My ultimate Swedish destination was Umeå – where you can get a ferry across the water to Finland – but I was starting to doubt my original planned route, it seemed too long and most of it was in the more developed eastern areas which after my adventure through the wilderness seemed a bit…tame.

There was another elephant in the room that was beginning to affect my decision making. Us Brits gets 90 days in the Schengen area before we have to get out and stay out (…for 90 more days). I hadn’t really let this impact any of my decisions until now, but I knew the deadline day would be somewhere in the latter half of July, which meant the 1-month countdown had begun; suddenly I was beginning to feel the light squeeze of time pressure.

Bear anxiety

The rain had subsided and the sun was back out, so I left Kallsedet along a gravel road that hugged the edge of a long lake heading east.

Sweden seemed less intimidating in the sun, and knowing I could turn around and head back to Kallsedet was a reassuring plan B if things went belly up. I wanted to do a wild camp, but there was still one thing in the back of my mind: bears.

I knew there were bears in Europe, although I have to hold my hands up and admit that I initially thought they were black bears – you know the relatively small ones that are afraid of their own shadow. But no, Europe is home to a subspecies of brown bear, and although they are much less aggressive than their north American ‘grizzly’ cousins, adult males can weigh up to 650kg and stand 8’2″ tall…that is eleven times bigger than me (by weight thank you; I may be a little short, but am definitely taller than 9 inches). The average adult female is 150-300kg which is still a big unit, and one that is perfectly adapted to their environment.

When you’re cycling through the deep forest sometimes the mind can wander, you begin to play out different scenarios and wonder how best to react:

- RUN/CYCLE: bears can run at least 30mph, the only half-chance would be if there happened to be a convenient long dowhill escape route on the bike.

- SWIM: bears love a good swim. I don’t know exactly how fast they swim, but it’s definitely faster than my shoddy doggy paddle, especially wearing clothes.

- CLIMB: yup, that bear is going to put you to shame. Just look at those claws, it’s playing on easy mode!

- FIGHT: Reckon you can take a brown bear in a fist fight? You better pray the bear backs down, because that’s a fight you will lose.

- THE OFFICIAL ADVICE: the internet will tell you bear spray is the best protection against an aggressive charging bear. But Eurasian bears are less likely to charge you in the first place, so most advice I’ve seen is to remain calm upon a rare encounter and slowly back away in the direction you came from. The Finnish government provides advice on a dedicated website.

So with bears lingering in the back of my mind, when I came across a perfect little camping area next to a hydroelectric dam in the sleepy village of Rönnöfors, I didn’t really mind that it wasn’t out there in the deep wilderness. I wasn’t’ a campsite, but it was certainly not ‘wild’ camping; the proximity to civilisation brought with it a psychological security blanket.

The further I rode into Sweden I began to appreciate how rare sightings actually are in this country, especially from the road. It would be incredible to see one…maybe a well fed one, without cubs, from a distance.

Rock art at Glösa

I didn’t come into Sweden with a plan to seek out rock art, but it soon became clear there was plenty of it around in Jämtland based on the tourist information boards and maps scattered around. There was one site in particular that kept popping up: Glösa.

The location helped with my route planning indecision, giving me a solid target and confirming that I would now definitely pass through Östersund. From my waterside camping spot I would head south to the satisfyingly named town of Kaxås, before taking the back road to Glösa and hopefully camp on the shores of the mighty (and curiously stag beetle shaped) lake Storsjön.

I was basking in perfect sunny weather conditions and the ride to Glösa was about as relaxed and enjoyable as cycle touring can get. Kaxås had a quirky cafe / homewares shop that seemed to actively disguise itself from passers by, and I spotted what looked like a family of emus tip toeing through a field of long grass (I assume they were cranes).

I was back on gravel roads and the terrain was getting hilly as the car park for Glösa approached. The site itself is on exposed bedrock at the top of a waterfall, surrounded by woodland. You wander down an idyllic farm track where well-groomed horses watch you intently amongst spring flower meadows.

The path leads into an area of pine woodland and you can hear the sound of cascading water emerge from an opening in the trees. The water has carved a sequence of smooth steps as it makes its way down the hill side, with an especially broad area of smooth bedrock exposed on the far side – this is the canvas our ancestors chose for their artistic expressions.

I’ve seen my fair share of rock art before where you really have to fire up the imagination to transform the scratchy squiggle in front of you into the subject matter, but not at Glösa. Well, they can’t quite work out exactly what species some of the figures are supposed to be, but they aren’t absurdly inaccurate like those medieval artists who seemed to paint from source material acquired via a long game of Chinese whispers. The central moose is unmistakable and looks to be next to a large net, possibly with another net on its back. It never occurred to me that hunter gatherers might use nets to catch large land animals rather than stalking them with arrows and spears etc., clearly they were a bit smarter than me.

Östersund

I decided to make use of the good weather and camp on the forested shores of lake Storsjön around 10km from the town, which was ok in the end but it took several attempts to find a spot acceptably far away from the forest’s abundant ant nests and their army of residents.

Östersund is quite a small city but a pleasant and clean one. The high street is colourful and has a relaxed atmosphere, and there is an undeniably high quotient of stylish and good looking people (I think it’s a Swedish thing). There was a surprising number of big, shiny vintage American cars like Cadillacs and Chryslers on the streets, not just in Östersund but across Sweden, although to my delight there were even more old school Volvo’s and Saab’s kicking around of course.

To celebrate being out of Norway I headed into town for a few beers on Saturday night, ending up in a rock/metal venue that opens till 3am. Given the late closing time I was waiting for proceedings to evolve from ‘bar’ to ‘club’ at any moment…but the music remained quiet, the conversation polite, and the dancefloor non-existent. It was pleasant an all, but a very different cup of tea to somewhere like Satan’s Hollow in Manchester – more Swedish, I suppose?

I stayed in a quirky hostel operated by the Nationalmuseum Jamtli, which has a significant ‘open air’ aspect where actors wander around in full 18th century costume, sometimes right outside my window. I was in some sense a part of the exhibit, although sadly they didn’t give me a costume.

A couple of nights in hostels had given my body a break from cycling and a chance to recover, which for me is one of the main benefits of spending time in cities. With the help of some self-administered massage, the perennial tightness in my quads and iliotibial band softens up and the dull ache in my hands subsides.

The wood amongst the trees

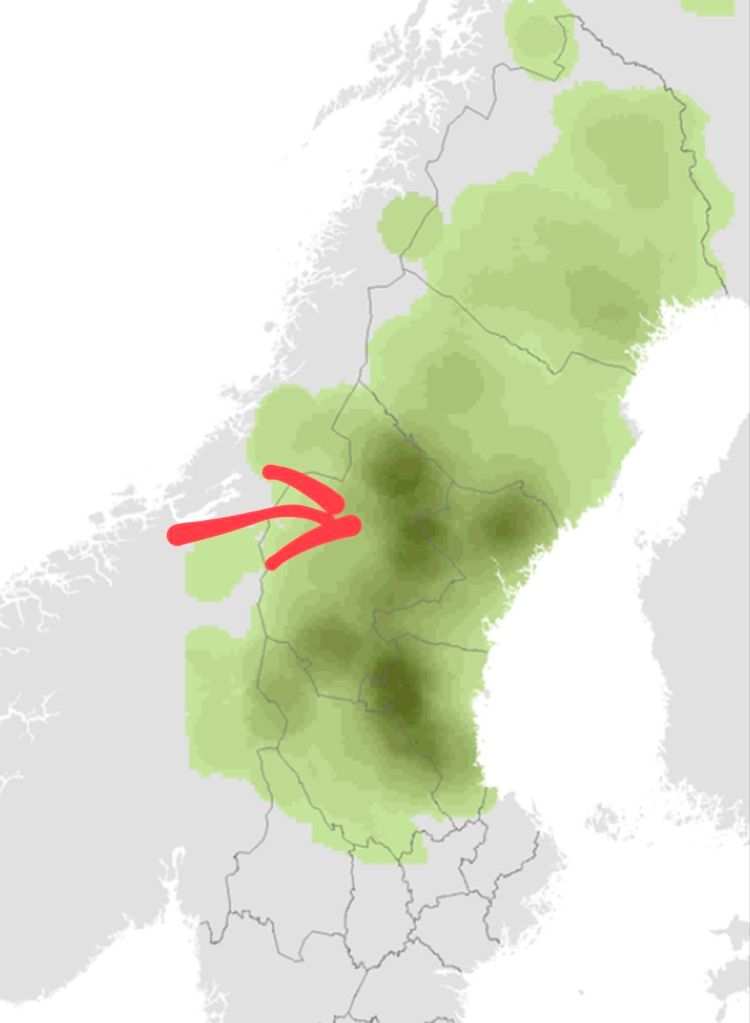

Nearly 70% of the land in Sweden is covered in forest, and I’ve seen one source estimate the total number of trees at 87 billion. The UK by comparison has only 13% forest cover, but apart from when I crossed the border most of the forest looked like it was being managed for commercial logging. Ancient woodland in the UK is one of our ecological treasures and I was keen to find the Swedish equivalent, if there was such a thing.

From what I can tell only a few percent of Swedish forest can be categorised as ‘old growth’. It seems that the best place to find these woodlands are in the protected nature reserves, and there happen to be one south of Östersund: Berge Virgin Forest Nature Reserve.

Berge provided another way-point to plan my trip around, which helped finalise my plan to get through Sweden – I would continue to ride south east and reach the city of Sundsvall, where I could catch a train up the coast to Umeå and take the ferry to Finland. Time was beginning to tick, so the train was necessary.

Berge is not a large forest and at first I wasn’t sure if I would be able to locate the alleged footpath from the map, but if you look hard enough you’ll find a roughly 1km long path that starts from a small layby beside an information board.

One thing the old growth forests have in abundance is mosquitoes. A face net would be well advised especially after a lot of rain. There’s a lot more life in that forest than mozzies though, and as soon as you walk in it feels different to the commercially forested sruff.

There was deadwood in every direction: on the ground, standing up, or sometimes leaning over precariously. The tree species were still mainly spruce, Scots pine and birch, but there was a good mixture of sizes with a few whoppers mixed in there. Much of the older looking deadwood was coated in lichens and mosses, with solid looking bracket fungi growing straight from the trunks above and dozens of soft bodied little mushrooms sprouting from the forest floor. Up in the canopy was a bird making a sound I did not recognise – was it a three-toed woodpecker? I don’t think so.

If you do make it past the mosquitos the path eventually leads to an opening in the trees where you are rewarded by a picnic bench. Worth a visit if you’re in the area, and quite different to the ancient woodland I’ve come across in the UK.

Completing the (reverse) pilgrimage to Sundsvall

The rest of my journey was propelled by a strong tailwind, which is superb until you try and put the tent up. I briefly considered the lakeside campsite in the small town of Bräcke but it had been transformed into a wind tunnel, so I headed back into the hills and found a sheltered spot next to a small outcrop of granite bedrock. It was by far the most ‘wild’ camp of Sweden to date, and whether the enormous moose skull that had been placed on the crown of a nearby plinth of rock served to ward off or attract evil spirits, perhaps I’ll never know.

I was still on the St Olavsleden path and approaching the end (or the beginning rather). As I rode those last few kilometres through an increasingly agricultural landscape I wondered about the differences between Sweden and Norway beyond the landscape. One thing that was not different was their obsession with pic n’ mix: they both go nuts for it, and you often see Lördagsgodis deals in the supermarkets with price reductions on Saturdays…a good day to stock up on your riding snacks! (I had to stop buying the chocolate and fudge ones to manage the urge to demolish my ‘on the bike’ snacks in the evening back at camp.)

Norwegian and Swedish seem to be mutually intelligible languages and many of the words phrases you learn in one will be understood in the other. You can in theory include Danish under that umbrella too, but I heard one Norwegian describe Danish to be spoken “like they have a potato in their mouth”, making it somewhat harder to dicipher.

But there are of course many subtle differences you pick up on. On a few occasions in Sweden I was passed by slow-moving pick up trucks with red triangles displayed on the back – I presumed they were hunting moose, until it happened in the middle of a city. It was actually teenagers (as young as 15) driving modified cars limited to 30km/h under a peculiar sort of provisional license that can be traced back to the 1920s. I would have loved that at 15, but at 38 I’m quite happy this is not a thing back home.

I kept seeing homemade signs for “Loppis” pop up on the side of the road in Sweden. Eventually curiosity got the better of me and I found out they were pointing to some kind of garage or yard sale. Now Loppis is a good word – maybe not quite turnip level good, but few words are.

My final camp en route to Sundsvall was at a small lakeside swimming area that is maintained to provide camping facilities for the St Olavsleden pilgrims, with a composting toilet, fresh water and even electrical outlets to charge up the devices. It was about as good as it gets, and I thanked the lady who maintained it as she came down for the morning tidy up – she was pleased I had camped because it meant the local Canada geese hadn’t spent the evening pooing all over her neatly mowed grass.

I spent the afternoon in Sundsvall doing absolutely no cultural activities whatsoever, opting instead to relax in the conservatory of a restaurant overlooking the square, doing my bit to bring down the average level of stylishness (and cleanliness) of their clientele to a more reasonable level. I got the evening train to Umeå and caught a few hour’s tent rest before a 5am start to catch the morning ferry to Finland.

—————————-

PHOTOGRAPHY: Trondheim to Umeå