When you search for guesthouses around the northern Azerbaijani/ Georgian border crossing you get virtually no results on the Azerbaijan side, for some reason all the B&Bs seems to be over the border in Lagodekhi. So although I would be entering the country after 9pm on a Sunday evening, confidence levels were high that I could find somewhere to stay.

The immediate barrier was a familiar one – I had crossed another border without sorting out my mobile phone data beforehand. No internet, no online booking. I would have to resort to the old fashioned way and bang on the door.

As it turned out the door banging wasn’t needed: I walked straight through the back gate of the ‘Old Wall’ guesthouse and poked my head into the open door, offering the only Georgian word in my vocabulary:

“გამარჯობა!”

What do you mean you can’t read Georgian? Ok me neither, got to love that script though.

“Gamarjoba!“

There was a lady recumbent in her comfy chair watching a small TV with an even smaller dog in the dimly lit outbuilding. It became apparent she wasn’t anticipating a Brit to appear out of nowhere because the poor woman almost jumped out of this life and into the next. I assured her I meant no harm and simply wanted to stay the night, and we agreed on 100 lari. I had zero lari, but convinced her I was good for it in the morning.

It was partly down to the guesthouse owners happening to be fans of The Beatles, but the contrast between where I found myself and where I’d come from was stark. It was like cycling out of Azerbaijan and into a leafy suburb of Oxford…with a few key differences of course.

There was a knock on my bedroom door, it was the landlady’s husband.

“Welcome, welcome! Would you like tea or coffee?”

It had gone 10pm by this point, so I went for the moderately less caffeinated option. He led me out to the patio seating area, where above our heads hung dozens of bunches of red grapes.

“Two more weeks and we will make our wine.”

I had entered Georgia in Kakheti, the country’s most prominent and historic wine producing region. I still hadn’t finished my cup of tea before my host poured me a glass of red, on the house. I got the feeling I was going to like this country.

Going steady

Azerbaijan was an incredible experience, but the heat and dehydration had pushed my body to its limits, so it was time to take it steady and allow my body to recover.

I spent the next week or so slowly meandering across Kakheti, first to a hostel in the picturesque hilltop town of Sighnaghi, then to the town of Kvareli that sits just below the foothills of the Caucuses, before settling in the small town of Kvemo Alvani (which seems to have almost as many street dogs as human residents).

It was good to be back in a hostel again – the first since Lithuania – and Nato & Lado at Sighnaghi is a particularly sociable one, helped in part by the free flowing glasses of local wine (and for those brave enough, the 60% ABV homebrewed brandy, chacha). Wine might not have been the ideal tonic to aid for my recovery, but at least I had my feet up in the peak afternoon heat rather than pedalling through it.

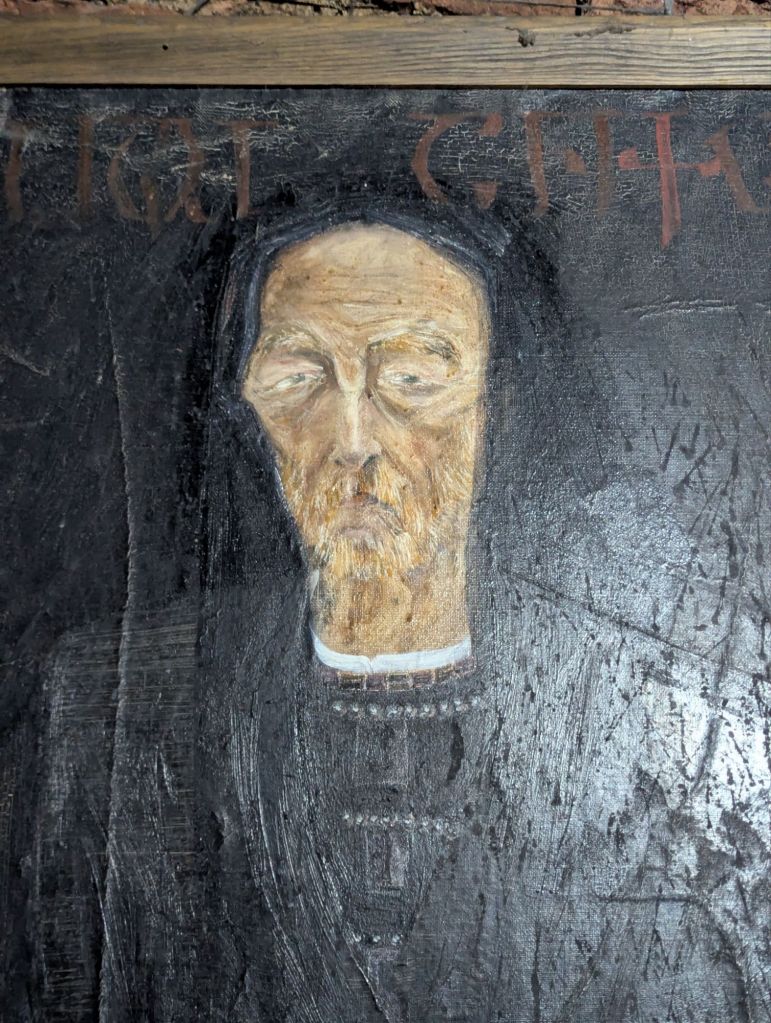

Upon entering Georgia it soons becomes apparent there is no shortage of churches and monasteries. They look quite understated from the outside, often with a rounded central tower capped with a conical roof, and are built in stone or brick with little in the way of exterior decoration. The magic of these buildings is hidden away on the inside: frescoes, often painted on every available square foot of wall and pillar.

Sadly, at least from what I saw, these frescoes can be in poor condition and in need of restoration – a complex and potentially controversial endeavour based on the shit show at Gelati Monastery – but even with the paint peeling off they are still well worth seeing. The churches are generally active places of worship, with orthodox priests in black gowns keeping an eye on proceedings. I never quite worked out if it was strictly prohibited to take photos inside the churches, but it didn’t feel like the environment to be getting the smartphone out.

The museum at Gremi is worth popping in just for the small collection of paintings of kings and queens. The portraits are painted more stylistically than their western European counterparts, making them look remarkably modern. All of the paintings had something in common: there was an almost gloomy seriousness about them. This same feeling could sometimes be felt out on the streets of Georgia too.

From foes to friends – the ubiquitous street dogs of Georgia

If you ever visit Georgia then you will quickly encounter the street dogs. They are unavoidable, whether you’re a dog lover or not – if you fall into the latter and are a bit worried about visiting Georgia because of the dogs, maybe hearing about my experience will put your mind at ease.

On a bicycle the roaming dogs can feel like your foe since half of them are usually barking at you. But for pedestrians the vast majority of street dogs behave like well behaved pets. They can be mostly found flopped on the floor in the shade, until they muster the energy to get up and have a sniff around the vicinity for some food. Sometimes they will walk up to you, but you don’t have to engage – if you simply ignore them they soon move on. You could always toss them a bit of food, but they might not leave you alone if you do!

I’ve never had a street dog invade my personal space by jumping up or licking me without invitation. If they ever get a bit too close (occasionally they look quite diseased) I just raise my voice and they back away.

It’s probably best to avoid petting them, although I sometimes do so with the most good natured (and relatively clean) ones, and remember to wash your hands if you do have contact. Avoid touching any animals when you have open wounds on your hands, and if a dog does ever scratch or (god forbid) bite you: go to the hospital, regardless of whether the dog has a ‘vaccinated’ ear tag or not.

Like I wrote about in the Azerbaijan blog, when you’re on a bike it’s a slightly different dynamic. It is common for them to bark, you simply have to get used to it. Sometimes they will run alongside you at high speed, not because they intend to maul you, but because dogs love to run. In running they are expressing a primal instinct and it can be spectacular to behold – I’ve had shepherd dogs bounding across the field alongside me over rough and uneven ground whilst I motor along at over 50km/h: they rarely even stumble.

The highest risk dogs are those that are trained to protect something: guard dogs and shepherd dogs. Sometimes you will pedal past a property with an open gate and the resident dog will greet you with a barrage of hyper-aggressive barking. Similarly with shepherd dogs, sooner or later you will encounter modern day cattle droving: the cows will be wandering along the road and it’s up to you to navigate through the herd. If there’s a lot of cows this isn’t always straightforward, and soon as you find a route through the beasts (ideally without being trampled or gored) the bipolar shepherd dogs who previously had no qualms suddenly decide you’re public enemy no.1 and make chase. Arseholes.

I grew to genuinely enjoy the company of Georgia’s street dogs, especially the ones I got to know a little when staying somewhere for a few days. The dogs have become embedded into the roadside environment and I rarely see the locals show ill will towards them (other than yelling at them to stop barking when trying to have a lie in). I know they will always bark at me when I ride past on a bicycle, and that’s fine, we can still be friends when I get off.

Tusheti – pushing the envelope of heavyweight cycle touring

The Greater Caucuses have some seriously chunky mountains, the chunkiest being Europe’s highest peak – Mount Elbrus at over 5,600m. I wanted to ride somewhere into the high mountains but didn’t have any intel on where would be best to go with my setup.

My research consisted of looking for squiggly mountain roads on Google Maps and seeing if any took my fancy. There were a few candidates, but one in particular had the benefit of being just up the road from my base at Kvemo Alvani – the road to Tusheti.

Tusheti is a remote region of Georgia nestled deep within the Greater Caucuses, bordering Chechnya to the north and Dagestan to the east. There is only one road in and out: 70km long, largely unpaved, often treacherous, winding its way through several climatic zones up to 2,826m at the top of Abano Pass.

The road is notoriously dangerous to drive on, with tourists recommended to pool together and use the local ‘marshrutka‘ taxi drivers rather than attempt the drive themselves. These marshrutkas usually take the form of a fourth generation Mitsubishi Delica, which has enough space for several passengers and their luggage whilst still being narrow and nimble enough to deal with the road’s narrower sections – plus they are probably quite cheap. Mind you, they look a bit on the top heavy side for my liking, and it’s good practice to satisfy yourself of your driver’s sobriety before you get onboard for the white knuckle journey.

But I hadn’t come here to get in a taxi, I wanted to cycle there. Why? Good question! Well partly because on a bicycle you are the one in control, not the marshrutka driver you just met. Bicycles are also relatively narrow, which takes away some of the jeopardy associated with passing other vehicles on the narrow stretches. But mainly because I’m cycle touring and this was an opportunity to really push the boundaries of what can realistically be achieved on my setup.

Modest beginnings

You’d be forgiven for thinking the Abano Pass is a walk in the park when you start off. After a 9km warm up (half of which was dodging JCBs through active roadworks) I reached the base of the climb at Pshaveli where the smooth tarmac road barely scrapes above a 1% incline. This flood plain is the end of the River Stori’s mountain adventure, but very much the beginning for Tusheti travellers.

The braided river channel was mostly filled with grey pebbles and boulders, the flow of water clearly at the lower end of its capabilities. Above the riverbank, large deciduous trees dotted the flat grassy plains as if I was making my way up the long driveway to a stately home in Shropshire, except I wasn’t about to be charged £12.50 for a coffee and a panini at the café.

As you move upstream and pass the final settlement of Lechuri the valley walls – covered in lush green broad leafed woodland – begin to move closer. The gradient begins to ramp up, the river sinking deeper and deeper into the valley floor below. Occasionally I would turn a corner and see the towering buttresses of rock that lay ahead – I still couldn’t even see the treeline before the mountain disappeared into cloud, and I knew the Abano Pass would rise above the trees. I couldn’t afford to dwell on what lay ahead though…not this early into such a long climb.

There is an ongoing government funded project to upgrade the road to Tusheti. I heard somewhere that they expected to get this finished by 2026, which seems a little…ambitious. There has been some good progress made on the lower sections to date, but if it’s anything like the A9 dualling project in Scotland they will leave the hardest bits until last, and take 10 years longer than expected.

Leaving the tarmac

On passing a roadside clearing full of beehives I wondered how easy it would be to tap some emergency honey if I ran out of food. Realistically, running out of food was never going to happen: I had enough provisions to last probably five days, but the possibility always lingers at the back of your mind when you enter somewhere remote.

Just beyond the beehives the road kicked up into a sequence of steep hairpin bends, or ‘switchbacks‘. It was the first properly steep section, and there was an increasing sensation of vertigo when glancing down into the valley below. Without warning, the smooth asphalt disintegrated into a well-compacted gravel road, and the real work would begin.

What followed was the most challenging physical endeavour of my life, and that’s coming from someone who did an ‘Everesting‘ on a turbo trainer during the Covid lockdown. Riding up a pass like this involves a lot more than just the cumulative elevation gain:

- 🚦Traffic: this is not a quiet country lane in Northumberland. The road can be alarmingly busy at times, with the marshrutkas and motorcyclists often arriving in waves. You need to remain vigilant, especially on the blind corners…you might even meet a Soviet truck with a cargo full of boulders!

- 🪨 Dodgy surfaces: The good news is that there are no significant sections of deep sand, but be prepared for a lot of loose rocks. The bedrock cuttings are rarely reinforced making the road extremely prone to rockfalls and even landslides. The fresh rockfalls often leave jagged lumps of slate sitting proud upon the road surface, ready to chomp into your tyre, or even break your wheel.

- 💦 Water hazards: I was worried these might be completely unrideable, but with the relatively dry summer conditions you can often walk the bike along the shallower edges. Sometimes though you just have to go through the middle…it is possible, just keep away from the edge and be prepared to get your feet wet if things start to go a bit pear shaped.

- ⛰️ Gradients: The majority of gradients I found to be just about rideable, albeit very slowly. There were quite a few short steep sections where I would ‘go into the red’ before easing off the gas again, but my ability to do this diminished as the day went on. Eventually I just got into the routine of pushing my bike up the steeper bits, but I never had to resort to removing panniers and doing a section in multiple trips.

- 🌡️Altitude: This one’s a double whammy as both the temperature and oxygen levels begin to fade. One benefit of my setup is it has all the clothing to survive spring in Scandinavia, so when I eventually decided it was wet and cold enough to dig out my waterproof jacket it was a big psychological boost. The depleted oxygen is a different matter – I seem to start feeling it around 2,000m, which made the next 800m quite an ordeal..

So those are the sort of things you’re dealing with. But it is also one of the most extraordinary landscapes I have ever set foot in. You can never really see where the road begins or terminates, it just seems to endlessly wind its way up a precarious mountain perch in both directions. Occasionally you get a glimpse of where you have been and the scale of it all, it is quite an experience.

Attempting the summit

So in a nutshell: I set off quite late (c.11am) intending to camp around two thirds of the way up, but just never found a camping spot that looked remotely appetising…it was all so, steep. Instead, I pushed on. The problem with this strategy is that I could no longer rely on the midnight sun of Norway in June for infinite daylight – by 8:30pm the sun had vanished beneath the hillside and it was properly dark.

I wasn’t overly concerned about darkness on its own, but coupled with the onset of thick fog from the rapidly assembling clouds, visibility had taken a nose dive. This isn’t really a big deal on the ascent because the pace is so slow, but eventually I would crest the Abano Pass summit and descend into the valley below – all it would take is one optical illusion and critical misjudgement before suddenly you find yourself cycling over a precipice, and a shortcut to an early grave.

To minimise this risk my plan was to sacrifice the break pads and descend less like Vincenzo Nibali and more like your grandmother; it would be painfully slow but I should reach the bottom alive, the benchmark of a successful descent.

At around 9pm after what felt like the longest steep section of the entire ascent (it wasn’t just the fatigue, it actually was), the road began to level off and I could start to make out the blurred edges of buildings. A motion sensor light flicked on and a warmly dressed young woman appeared in the door of a small kitchen.

“Oh my gosh, are you alone? It’s so late!”

“Yes it’s just me, is…is this a café?”

Café above the clouds is run by Daji, a remarkable local woman who lives at the summit of Abano Pass for half of the year selling drinks, snacks and various handmade garments to the dozens (even hundreds?) of people who stop by every day on their journey in and out of Tusheti. But in that moment, Daji was more than just a hardy café manager, she was my mountain top guardian angel.

“You mustn’t go down into the next valley, there are shepherd dogs there. If you try and make a tent they will get angry.”

With this new nugget of local intel, who was I to argue? I wasn’t quite out of the woods yet however.

“I will show you where you can pitch a tent here, do you have a head torch?”

I did have a head torch – but the batteries were flat. I don’t know if it was the altitude or the 10 hour climb I had just ridden, but I couldn’t remember where my spare AAAs were stashed.

“Don’t worry, you can borrow mine. Just give me it back in the morning.”

So I took a seat in the cosy warm seating area, ate a huge slab of plum cake, and drank a sugary cup of black tea before putting up my tent on a flat (if somewhat stony) shelf of land just behind the café beside their solar array. It was dark, windy, raining, and I had to use boulders as hammers to get the pegs into the ground…but once up it was solid, dry, and actually a little nostalgic to be back in my canvas home for the first time since Lithuania. And besides, once you’re on the airbed you can’t feel the stones anyway.

I treated myself to a solid 9.5 hours before getting out of the sack and handing my borrowed head torch back to Deji. Not before another mega slice of cake of course, that stuff is seriously moreish.

The rest of the ride was really quite enjoyable, mainly due to the assistance of gravity. After negotiating the high altitude switchbacks the valley narrows and you follow the Chabalakhi River as it cascades through the gorge further into Tusheti. The broad leafed trees had been replaced by forests of pine, it was very much a different ecosystem; Tusheti looks and feels different to the other side of the pass.

Omalo

Omalo is the largest settlement and effective capital of Tusheti. In the photo above it actually sits on the other side of that hill on the left. There’s no bridge, ropeway, or zip line across the gorge though – you need to descend down to the river and pedal your way back up a final set of switchbacks before reaching civilisation.

I’m unsure of the geology behind why Omalo is so much flatter and more hospitable that the steep mountain slopes that dominate the Greater Caucuses (glaciers presumably?), but it is a bloody good feeling when you emerge from the claustrophobic valley roads onto those big open plains. With its free roaming horses, rustic villages, and hilltop stone towers – surrounded on all sides by a skyline of high mountain ridges – Omalo is about as close to a fairy tale village as you can get. Maybe that will change when the road is fully upgraded, but I hope not.

Omalo is a popular starting point for the adventurous hiker. A popular route is the 5-day trek to the village of Shatili, and there are new routes being developed by the Trans Caucasian Trail and their network of volunteers (I met two of their staffers as they were recovering from an episode of food poisoning during a route reccy, the poor sods!). But after the exertions of merely getting to the place, I was quite happy just pottering around the local area.

On the morning I was planning to leave Omalo I met Mike and Callum – a Kiwi and Aussie – who had been riding bikepacking setups along some even more extreme routes. They were clearly going to be faster than me so we agreed to meet up the next day, that way I could get an afternoon’s head start.

I camped at the foot of the first major set of switchbacks leading out of Tusheti, only to be woken two minutes before my alarm by the unmistakable bark of a shepherd dog.

“Go away dog” I muttered under my breath, more of a prayer than a command. It seemed to work though; the dog moved on, and my morning routine could be carried out in peace.

I ended up getting about a 10 minute headstart on my friends from down under on the climb, a gap which they soon closed. We met at the summit where they were ready to order a second round of cake.

The descent from Abano Pass heading out of Tusheti is not to be underestimated. You just can’t maintain the same sort of average speeds that come with asphalt roads, and if you share our luck it might just piss it down for the duration.

I think it took me around 2.5 hours or so to reach Lechuri, by far the longest time I have spent descending, ever. It might be physically easier than going up, but that is a long time to be in full-concentration mode – the hazards come at you faster on the way down, and you’d best keep an eye on that 200ft drop into the canyon below.

There was a phrase that kept cropping up in my mind on the descent, which maybe gives some insight into the downhill experience:

“Like driving a double decker bus down Mount Doom on a rainy day in Mordor.”

Out of the frying pan and into Tbilisi

Tusheti had taken its toll on my body, bicycle and even the panniers. My muscles were aching, bolts had come loose, and everything was coated in a film of beige mud. Just to top things off, when I was away from the bike for 15 mins an opportunistic street dog got its head into my ‘food pantry’ pannier and snaffled the contents, leaving a mixture of cake crumbs and slobber.

After a full deep-clean and calling by at a roadside hardware shop to find a missing mudguard bolt replacement, I began to head west on a two day journey towards the capital. Day one was a little more hilly than I would have liked but otherwise ok, ending in a very homely guesthouse at the village of Tushurebi. Day two was to be mostly downhill, so surely that would be easy going, right? Right!?

The attack plan was to avoid the busy roads going into Tbilisi, and instead approach from the north following a gravel trail that would wind through Tbilisi National Park.

If you ignore the fact my GPS thought it was January 2006 and was getting itself in a right old muddle, everything was more or less going to plan…until entering the National Park. Within minutes I was heaving the bike inch-by-inch up a desperately steep case of hike a bike.

At least I could push my bike up the first hill. After a small stretch of rideable gravel the trail took a beeline over a sequence of hills (see photo above) and I had met my match. The extreme gradient meant it was simply impossible to push the bike anymore; I removed every pannier except for the handlebar bag and began the process lugging everything up in batches. At least when I did this back in Norway it wasn’t like an oven!

After an awful lot of heavy breathing and heavier swearing, I summited the final hill and immediately re-routed to the nearest way out of Tbilisi National Park. Due to the GPS malfunction I was relying on the Google Maps ‘walking’ route, which got me out of the hills ok, but around 15 minutes after entering the city itself I found myself cycling down a slip road towards the centre of a six lane motorway. Not wanting to end it all just yet, I pulled onto the embankment, turned around and called into service a brand new mode of transport for the tour: a taxi.

Tbilisi was the first major pit stop since Baku, and at seven days the longest so far. I felt more like a short-term resident than a tourist, taking the opportunity to get my bike serviced, do laundry, and catch-up on blog writing & video editing.

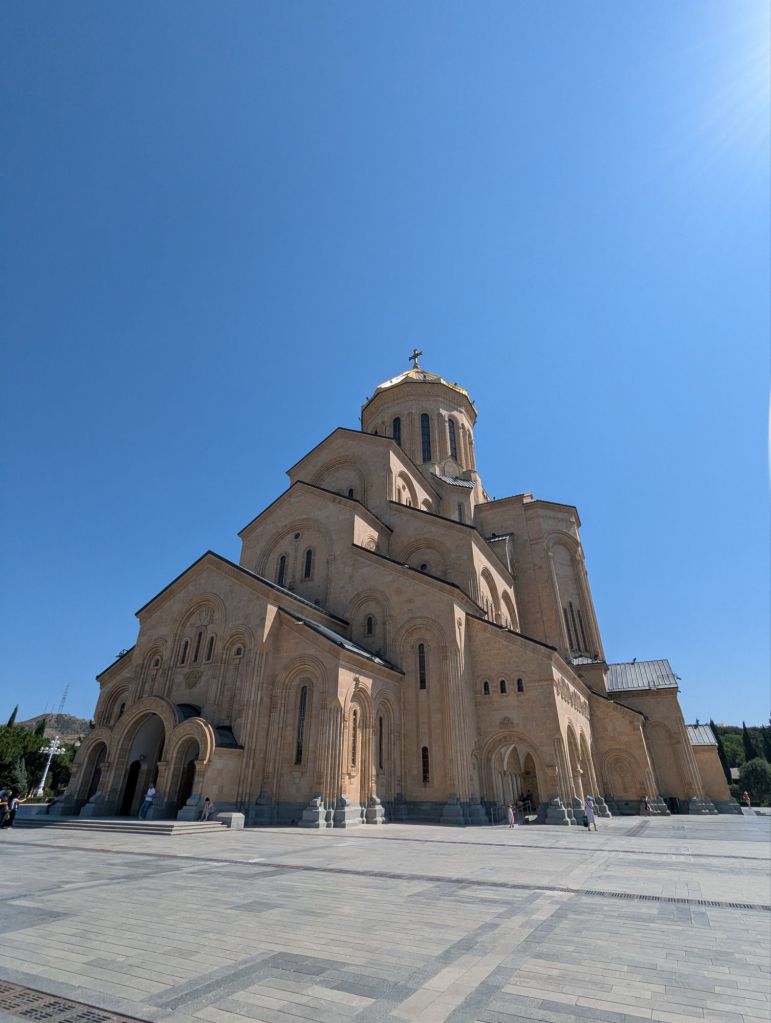

I did have a good wander around the city though, and managed to achieve my sole cultural objective of attending the cathedral’s Sunday morning service, where the resident choir sings ancient polyphonic Georgian hymns. The soft harmonies resonated gently around the immaculately frescoes walls of the 21 year old cathedral; Orthodox worshipers stood listening side-by-side with visitors in the pew-less nave & aisles, the faithful occasionally taking time out to kiss one of the gold-leafed icons hung from the candlelit walls and pillars. I’m not a religious man, but I’ve sung in a western choir for many years where much of the choral repertoire is structured as a Catholic mass, so it was a novel experience to hear the eastern equivalent for a change.

That’s enough rabbiting on I reckon, so let’s close out with a few photos from around the vibrant and occasionally bonkers city of Tbilisi.

——————————-

PHOTOGRAPHY: Georgia

Leave a reply to softlybbc8d8cbad Cancel reply