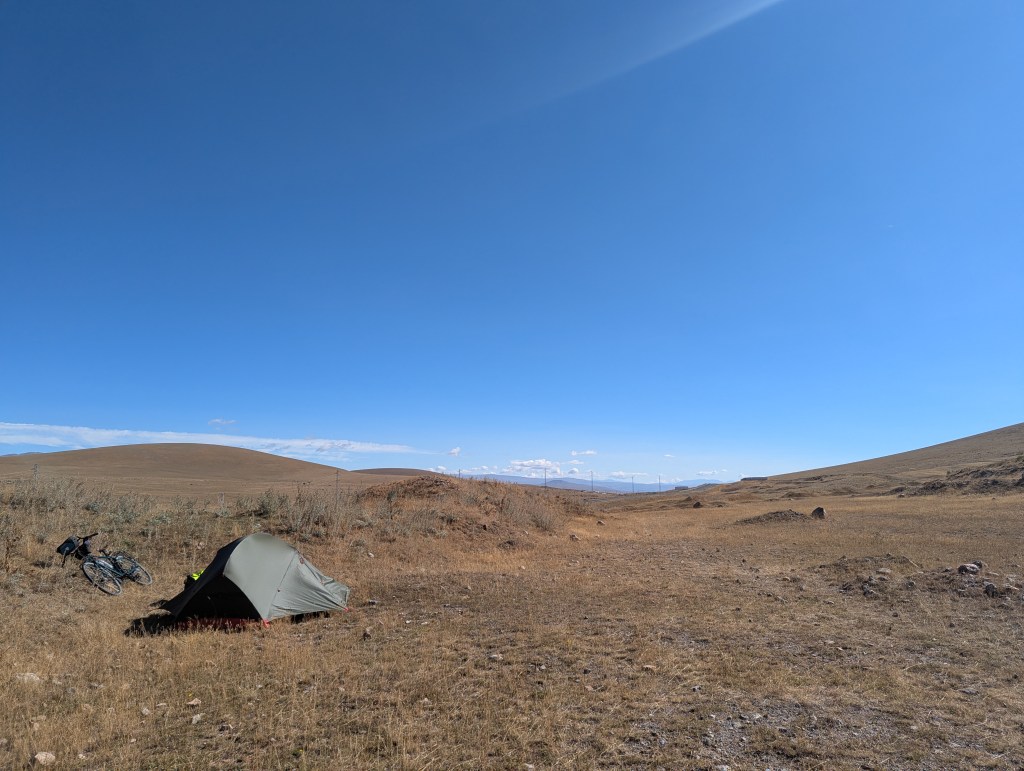

It’s gets cold at night on the high mountain plateau, but wrap up in enough layers you can lay down and enjoy the solitude. There were no strange animal noises, early morning tractors, or herds of sheep – it was just me, the crickets, and occasional distant call to prayer. Just don’t expect much in the way of trees to shelter from the morning sun up here.

Heading for the small town of Göle, I can’t have ridden much more than ten minutes before what appeared to be a small group of soldiers in combat gear waved at me to pull over and stop. This is the Gendarmerie, Turkey’s armed internal security agency. It was all fairly routine, just hand them your passport and if they’re in a good mood you might get a cup of tea in return. On hearing I was headed for Erzurum, they allowed passage on one condition:

“You must eat ‘jah kebab’ in Erzurum…best kebab in Turkey!”

Eating kebab is a Condition of Carriage I can live, but best in Turkey? That’s a strong claim, but one worth investigating.

The road began to follow a small river and we began to carve our way gently downhill into a small valley, where the left side was carpeted in a dense monoculture of pine. The wash of green made me realise how devoid of forest the steppe landscape really is; you wouldn’t look twice at such an ordinary sight in Scandinavia, but out here it feels precious.

I called into the centre of Göle in search of lunch where I was quickly mobbed by a gang of young boys outside the A101 discount grocer. The arrival of a multi-coloured Brit on two wheels was a solid dose of entertainment for the youngsters, but they were good kids and keen to show me the best lunching spot. The pack leader led me into a worn out looking indoor shopping clad in sun bleached metal and glass to his recommended venue – a kebab house, naturally, where the most popular dish was a chicken shawarma served in the same crusty baguettes of white bread that you can pick up beside the front door in every grocery store. At 80 lira (£1.40) a piece it was the cheapest kebab of the trip but by no means the worst. No matter what country you are in, never underestimate an indoor shopping precinct if you’re after a cheap sit down meal…the more discount shoe shops and knock-off football shirt vendors the better.

I was starting to get the hang of prices in Turkish lira, but hadn’t quite clicked that the ’50’ coin in my pocket was denominated in kuruş, i.e. 1/100th of a lira. Kudos to the Göle town centre toilet attendant, who politely corrected me when I tried to pay the 10 lira entry fee with 50 kr coin (only nineteen coins short). It’s a good job this trip wasn’t twenty years ago when, for a brief period, the old Turkish lira was simultaneously in circulation, coming in at 1/1,000,000th the value of the newly re-based currency after decades of chronically high inflation; trying to pay with cash that is a million times not enough money really could get awkward.

Saying your goodbyes

Learning to say goodbye is pretty fundamental when entering a new country. With basic phrases, I have always tended to reach for a quick Google Translate, but you can sometimes come a cropper doing this. Let’s take goodbye as an example:

Seems simple enough, goodbye translates as güle güle, and you hear this phrase all the time from shopkeepers, hotel receptionists, kebab vendors to say goodbye. Now the confusing bit: the word for ‘goodbye’ in Turkish varies depending on whether you are staying put or leaving to go somewhere. Güle güle is said by the remainer, but the phrase for the leaver is hoşça kal. Not exactly the most egregious language cock up, but it probably explains the wry smiles I would sometimes get from locals as I botched the farewell.

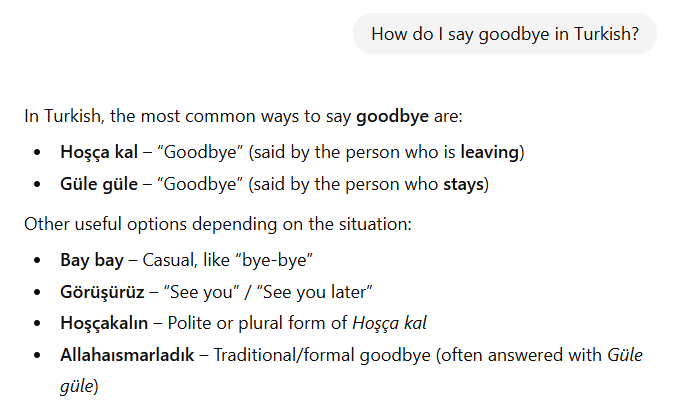

To be honest this pitfall could have been easily avoided by doing some basic research, but the speed and convenience of Google Translate is hard to resist, at least until it lets you down. In the 2020s we have a novel alternative to Google Translate: Large Language Models (LLMs), aka ‘AI’ chatbots. There’s an understandable backlash emerging against AI slop – i.e. low effort, garbage content infiltrating the internet from generative AI models – and I don’t exactly fist-pump the air in ecstasy to celebrate the latest crowbarring of AI into another product or service; even WordPress (the platform I use to write these blogs) has an AI assistant on the formatting ribbon where, amongst some relatively benign options like checking spelling and grammar, an author can choose to ‘expand’ upon the text they’ve already written…hmm. I can assure readers that AI generated text has no place in this blog, but that’s not to say LLMs don’t have their uses, including for travellers.

One advantage LLMs have over traditional machine translation used by Google Translate is that when prompted for phrases, they will respond using full sentences and formatting, allowing them to provide contextual information. Remember that when training models like ChatGPT, OpenAI and co have scraped all the language learning websites, forums and textbooks they can get their hands on, so the responses tend to pick up on frequently discussed nuances – like when to use güle güle and hoşça kal:

It’s worth noting that AI chatbots use orders of magnitude more computation than apps like Google Translate, so can be a bit of a sledge hammer to crack a nut. Probably best reserved for when traditional methods have let you down rather than a first port of call.

In a world where people engage AI chatbots instead of a human psychiatrist, lawyer, and even significant other, using language models to help with languages feels almost quaint at this point. If AI translates your phrase wrong, the chances are a shopkeeper laughs at you; getting your psychological treatment wrong could be more consequential.

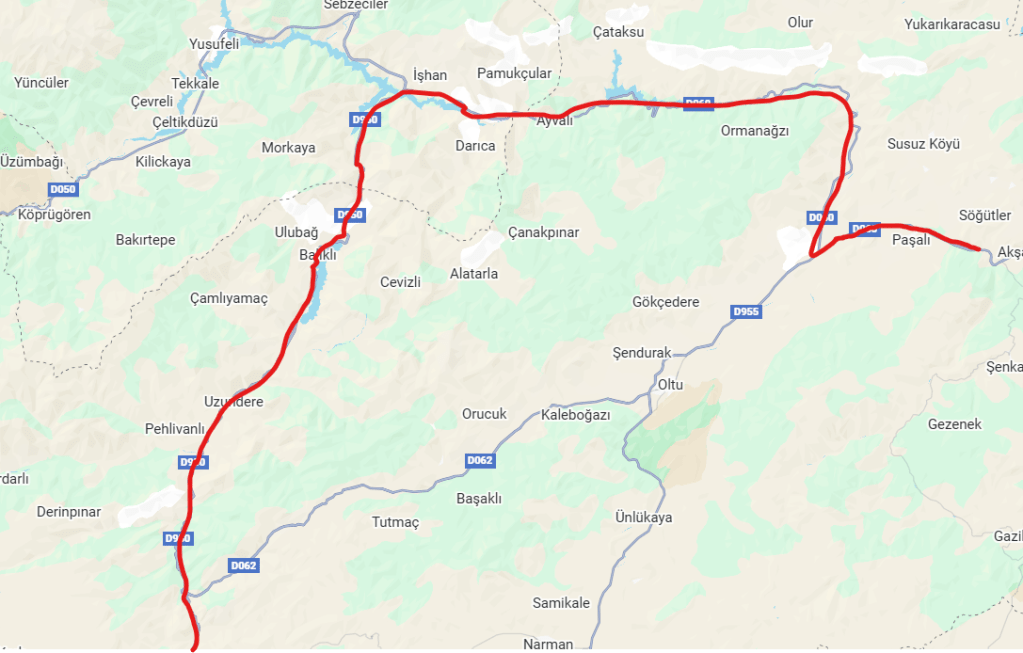

Ok, back to the real world. I said my grammatically flawed goodbyes to the friendly people of Göle and continued along the road heading south west. It was finally time to lose some altitude via a sweeping 1,000m descent down a rocky canyon.

Line management

In cycling they talk about the importance of the line, i.e. the path on the road ahead that your wheels will roll over. A poor choice of line will bounce you over stones, into potholes, and through murky puddles of ambiguous depth, whilst good lines bring a smooth ride and less punctures. It’s always worth keeping half an eye on what’s coming up ahead and adapting your line accordingly.

Sometimes the hazards are biological. Billions of insects make the dangerous journey across our roads everyday, where if they aren’t liquified by a car or gobbled by a bird, they might just end up wandering into your line. You mostly end up dodging the usual suspects – beetles, snails, caterpillars, etc. – but every now and then something more unusual crops up and you just have to get a closer look.

Not far beyond the village of Akşar on the long canyon descent, there was large and eerily fast-moving critter making its way across the road and towards my line. It was a camel spider, not that I knew that at the time, it just looked like the biggest spider I’ve ever seen outside of a glass enclosure. It turns out they aren’t venomous, not technically spiders, and are basically harmless to humans…but still, I wouldn’t fancy waking up to one on my pillow in the morning.

Into the valley

At the confluence of two streams I hung a right off the main road headed towards a network of long, winding reservoirs. The idea was to ultimately visit Tortum Şelalesi, a waterfall that looked to be the area’s main tourist attraction, before continuing on south towards Erzurum.

A few miles down the road a car pulled up beside me and the front passenger tried (and failed) to hand me a bottle of water Tour de France style. The car pulled over and the occupants identified themselves as a Turkish singer and his entourage – it’s always nice to chat to folk, but I did notice one of them was filming our chat. Was this was my debut on Turkish TikTok? God knows.

I setup camp beside the Byzantine ruins of Erkek castle, the modest remains of which sit perched on a hill standing proud above the floodplain. There had been plenty of flat, green grass around for camping opportunities, but most of the fields were filled with fruit trees ripe for harvest making them a bit more prone to farmer conflict. No one would disturb me here.

A small thorn had burrowed itself below the skin of my finger during an evening scramble up to the castle, requiring some careful tweezer work back at the tent. Now at the more gentle altitude of 1200m the 5am temperature dip was softened, so less tossing & turning and more quality rest. When the sun eventually rose above the valley walls, trees lining the banks of a nearby stream provided the perfect morning shade. This is my kind of wild camping.

The green oasis of fruit trees and fields that hugs the river’s edge had been replaced by the green water of our first reservoir. The water levels were quite low, so low in fact that the remains of abandoned villages were rising into view.

With a population of over 85 million in such an arid climate, it’s no wonder Turkey has so many reservoirs. They provide hydroelectric power too, with over fifteen times the installed capacity as Britain. Turkey isn’t shy when it comes to major construction projects, so it’s not unusual to share the road with large, noisy HGVs like cement mixers, although you don’t normally end up in control of one…

The driver gave a double-handed wave for me to stop at the roadside. He was adjusting something at the vehicle’s rear but needed a helper. Despite the language barrier it was clear my job was to hop into the cab and press down on the brake: on the sound of a *hiss*, simply release the brakes and all would be well. If the brakes fail and the cement mixer rolls towards the reservoir, I could always dive out of the open door, roll along the floor, and hope for the best. The important thing is I was wearing a helmet.

After five minutes of tinkering the truck was fixed and I could stand down from duty. We had the usual chat about where I was coming from/going to, before the driver smiled and asked an unexpected question:

“Erdoğan, good president?”

I had visions of living in Glasgow back in 2012, when I wondered how best to answer the question “Celtic or Rangers?” without getting my head kicked in. I’m not convinced “neither, Scottish football is dogshit” would be the perfect Get Out of Jail card, but at least it would be honest. Nobody ever asked me that when I lived in Glasgow, but was this a similarly loaded question?

“Oh, I don’t know really, he’s not my president”, shrugging my shoulders in neutrality. His smile widened and we both had a good laugh, but I never worked out if he was for, or against the main man.

Marriage Counsel

Shops are few and far between on the reservoir road, so on rolling into the small village of Ayvalı around 2pm it was finally time for lunch. Rural Turkish shopkeepers tend to be moustached men in their 50’s, but the chap working in this shop was younger than most, in his late 20’s at most. I brought my bread and beef sausage to the counter and asked to pay by card; the shopkeeper begrudgingly obliged, as if I’d just ruined his day. Regardless of the country, the cheerfulness of males in the company of strangers generally peaks around ages 8-10 before plummeting in their teens, until slowly rising once again as they mature into old age (with notable exceptions, obviously). I suppose what I’m saying is that young men often have their guard up to begin with; maybe it’s down to overly sensitive threat detection.

I perched on a step outside the shop front under the shade of an Algida (aka Walls) ice cream parasol. The shopkeeper came outside to chat with a couple of friends over a cigarette. It wasn’t long before they wandered over for a chat, wondering if I knew another cyclist who had come through in the last few days and managed to break their bicycle (I didn’t), and we laughed about how painfully mountainous Turkey is for cycling. Every now and the man would point his phone in my direction and the Google Translate text-to-speech voice would start talking, then I would do the same back.

“Are you married? Do you you have children?”

“No, I’m not married. A trip like this would be difficult with a family, unless they came along! Are you married?”

“No, we are all single!” he declared, as his friends burst into laughter. “In Turkey, the girls these days want to wait a long time before marriage. Many move to the city, Istanbul.”

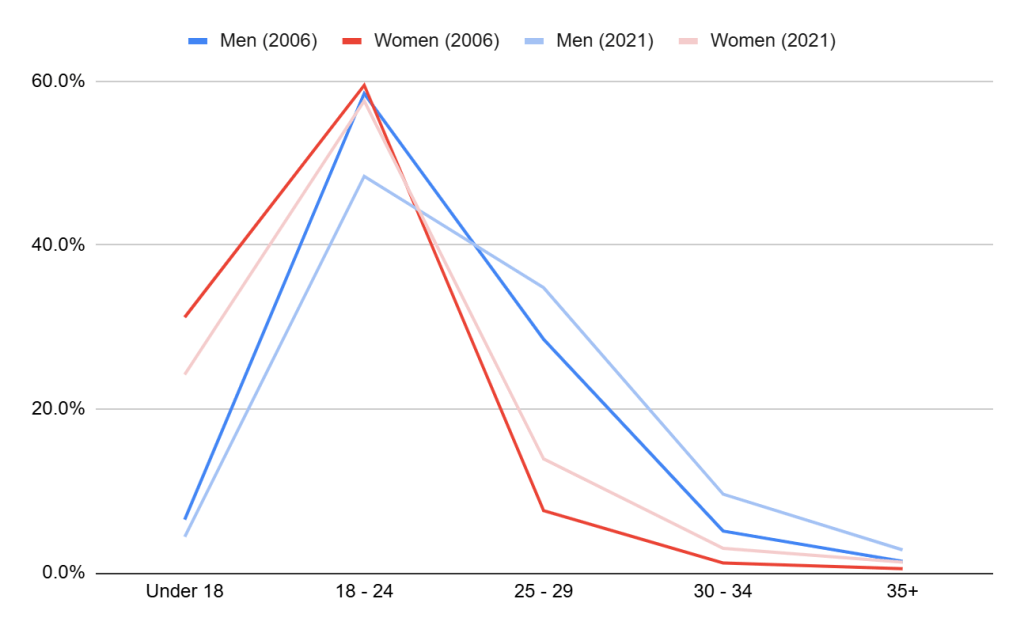

Despite the laughter, you could sense a hint of disconnect between the young man’s life expectations vs reality, and perhaps more so the expectations of his parents and grandparents in the culturally conservative rural Anatolia. Anecdotes like this often make me wonder what the data has to say, so I’ve dug into the latest Türkiye Family Structure Survey and some similar research from 2006 to try and find out.

(Source: Research on Family Structure in Türkiye – Findings, and Recommendations; Türkiye Family Structure Survey 2021)

In a nutshell, our shopkeeper was right: as of 2021, Turkish women are less likely to get married under the age of 25 and more likely to get married above this age than they were back in 2006. The same is also true for men, but there is key difference here between the sexes when it comes to child marriages (under 18). Girls remain around five times more likely than boys to be married in childhood, although child marriages have reduced across both genders by around a quarter since 2006. Less men are getting married aged 18-24 than before, yet it remains the most common age bracket for first marriages in Turkey. These numbers are for Turkey as a whole – I couldn’t find gendered breakdowns by region, but people generally marry older in Istanbul and the coastal regions than in Anatolia.

By far the main reason stated for not getting married in the 2021 survey was to prioritise education, in both men and women. I doubt delaying marriage for an education was a viable option for most youngsters growing up in 1950s Anatolia, especially girls, and by the 1980s those women who did want to study faced an extra hurdle: a headscarf ban. For me this is one of the most intriguing peculiarities of modern Turkey: the military-backed secularists prohibited the wearing of headscarves in universities, schools, courts and the civil service, effectively excluding women from conservative religious communities like rural Anatolia from higher education and working these professions. Erdoğan’s government has been gradually lifting each of these bans since the 2010s – so in this regard there are more opportunities nowadays for young women to pursue alternatives to early marriage in Turkey, however, this may feel slightly at odds with the socially conservative, Islamist values championed by Erdoğan’s government, where pressure is exerted on women to prioritise family life.

We Brits on the other hand are ahead of the curve when it comes to delaying marriage. If you used the same age brackets as above, 35+ would come out top for men and 30-34 for women; there were even 63 men and 26 women who got married for the first time aged 80 and over according to the latest data for England & Wales. When you think about it, care homes are a bit like university halls with inhouse bingo, no wonder the residents sometimes get hitched – no arguing about the chores, that’s all taken care of! It sounds rather good to be me, although it requires living to 80 first..

I bid the guys farewell and set off towards the next reservoir.

The Waterfall

The geology was getting more dramatic by the mile as the road crossed into the province of Artvin. . The steep topography and flooded valley floors has left the road engineers few options but to build a network of long tunnels flanking the water’s edge. This is the eastern end of a colossal reservoir created by the Yusufeli Baraji, which at a 270m high is one of the tallest dams in the world. It is named after the town of Yusufeli whose 7,000 residents were forced to abandon their houses, shops and farms in 2023 when the valley and everything within was inundated under two billion tonnes of river water.

Even Norway rarely has this many tunnels lined up in a row, around ten in total on this section and up to around 3km in length. They are actually quite refreshing after a day of relentless sunshine under a cloudless sky, and the traffic out here in the sticks is quite tolerable.

Sadly the Yusufeli dam wasn’t on my route, which had now turned south up a steady climb back into Erzurum province. A small brown tourist sign to Tortum Şelalesi pointed me down a side road towards the car park. It was 5pm on a Sunday afternoon and the place was sprinkled with Turkish families, couples, groups of friends – even a bride & groom had walked down the long and often crumbling concrete stairs to get a better view of the falls. By now the waterfall was in late afternoon shadow, but the golden evening light was catching a column of mist as it rose above the gorge.

It’s normally best to listen to your head over your stomach, but sometimes the hunger is too powerful. The sensible option would have been to find a camping spot before darkness set in, but it takes a while to properly enjoy lamb kofte, especially when the complimentary rounds of tea keep coming. t was pitch black by the the time I got back in the saddle, wishing that a good spot would magically reveal itself – a wish that was granted in the form of a picnic area 5km down the road. It was not as private as the last couple of spots but benefitted from drinking water on tap and a choice of gazebos ideal for breakfasting. Whether the person who knocked over a large metal dumpster-style bin beside the entrance at around midnight did so on purpose or by accident, the ‘out of tune gong’ explosion of noise made for a better alarm clock than lullaby.

An offer you can refuse

Today’s goal was to leave the valley of reservoirs and continue south-west to the city of Erzurum. After three days of camping on the trot the prospect of a bed and shower was quite appetising, and the city was now well within a day’s riding. The map revealed a couple of challenges ahead: a hairy looking junction on a dual carriageway, and a hefty 900m mountain pass.

The dodgy bit on fast road junctions is an exit slip road when you want to carry on straight ahead, where the exiting traffic is going like the clappers and unlikely to a expect a cyclist to suddenly materialise on a collision course. On this occasion the traffic was calm, but you might have to stop or even exit down a road you didn’t plan to go down if it gets you out of a pickle.

That picture pretty much sums up my experience of using a Jetboil for anything other than boiling water – take your eyes off the ball for one moment and the fecking thing erupts on you. Coffee mishaps to one side, progress was good and the road slowly began to snake its way up the valley towards Erzurum. The screaming diesel engines of 40 tonne trucks don’t make for the most peaceful of company on the road, but where there are HGVs at least you know the surface will be smooth and the gradient tolerable. With plenty of food and water, all I had to do was chug away and enjoy the view.

I was fairly content making my way up the hill, but maybe to passers by I looked like a man in need. An articulated lorry pulled over in the shoulder ahead of me, blocking the path. The driver hopped out and met me at the back of the trailer.

“To Erzurum?”

“Yes”, I nodded.

“Ohh, very big hill! Please, get in the back”, he pulled a latch and the trailer’s rear door swung open.

It was a kind offer an all, but I just wanted to crack on under my own steam. Upon declining, he seemed to assume I was just being polite and placed his hand on my handlebar. It was one of those awkward moments where it would’ve been handy to know more of the lingo, but he seemed to get the picture when I barked “Bicycle!” in Turkish whilst pointing at my chest then towards Erzurum.

I pushed the bike onto the verge and around the truck before continuing on, 99% confident this man was genuinely trying to help, rather than kidnap me. Thirty seconds later the same truck crawls past and once again pulls over in front; confidence was down to 90%. The driver hopped out, but this time he had a carrier bag in his hand.

“Please, for you.”

It was a punnet of juicy red grapes and two cold bottles of water. Not a kidnapper, just a (very determined) good bloke.

Erzurum creeps into view as soon as you crest the climb. It’s still a fair distance away at this point, but with a generous serving of downhill and flat riding including a good chunk of hectic city riding before reaching the centre. My strategy was to keep riding until the narrow inner city streets became too chaotic and confusing, then finished the journey on foot to Otel Çınar. Now where’s that shower?

Leave a comment