Route planning is a savoured pass time for some and a necessary evil for others. I enthusiastically fall into the former, but it can occasionally induce a headache when the ‘perfect’ route in your mind collides with the constraints of our imperfect world. Armenia has an abundance of such constraints.

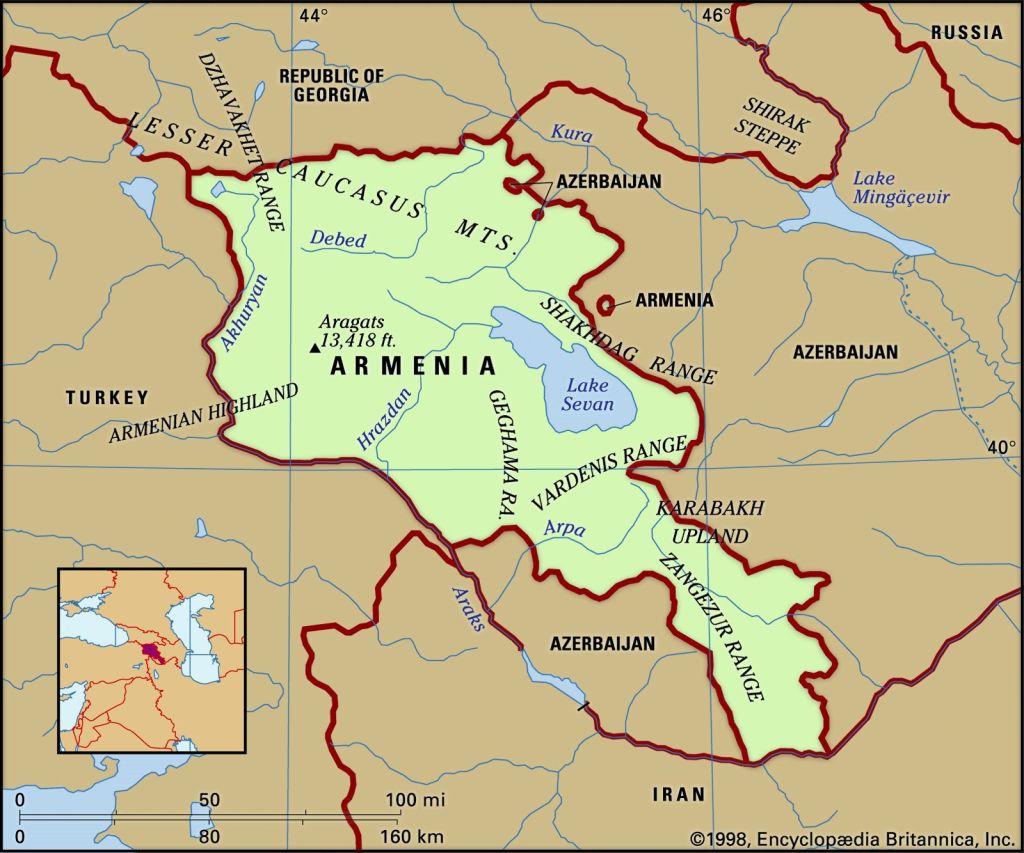

So from Georgia, unless you plan on entering Iran, Armenia is a bit of a cycling cul-de-sac. My ideal route would have headed out of the capital Yerevan and crossed into Turkey just above the northernmost tip of Iran, but clearly that was not an option. Instead, I would enter Armenia from the east and eventually exit back into Georgia in the west.

Escaping Tbilisi for the border

Getting into Tbilisi was such an ordeal it culminated in calling upon an emergency taxi. This turned out to be so cheap and easy it was tempting to repeat the procedure on my way back out. Concerned I might be morphing into a lazy slob after seven days out of the saddle (and numerous McDonald’s) I closed the Bolt app and rode my way out of Tbilisi following the sadistically steep concrete road that rises out of Ortachala district, past the heavily fortified British Embassy, and on to the exclusive Tbilisi Hills gated community and golf course. The switchbacks here rise up to 20%, so be prepared to push!

You’d best savour the panoramic car park views at the golf club because all that hard earned altitude is about to rapidly surrender when the route descends to join the main road between Tbilisi to Armenia. The highway is mainly downhill, mostly straight and makes for quite a swift ride – it is also packed with lorries, vans and cars hooning their way between the two capitals, so not exactly the most peaceful of journeys, but when it comes to border crossings the choices are often limited. There are one or two stretches where you can slip off the main road onto an adjacent side road to take respite from the traffic, just try to ignore the piles of dumped construction waste and bloated carcasses of fallen livestock.

Border crossings always come with a hint of anxiety, I think it’s how the border officials like it. It’s fair to say my anxiety levels were running a tad higher this time due to the fresh stamp in my passport from Armenia’s long-time nemesis, Azerbaijan. Sure enough, the Armenian border official flicked through my passport and gave me a stern look.

“Why were you in Azerbaijan?”

I glanced down at the bike then back at the militarily dressed man, and tried my best not to sound sarcastic:

“Tourist. I’m travelling through the Caucuses on the bicycle“.

It’s almost tempting to come up with some lame excuse for why you chose to visit Azerbaijan – ‘It was the only flight available, honest‘ – but it’s really not necessary. I reckon the Azerbaijan trip landed me with a few extra questions (e.g. ‘Do you have a hotel booked?’, ‘Do you have any friends in Armenia?’, erm…are you my friend?), until eventually he handed back my passport.

“Welcome to Armenia“.

As usual, the anxiety was just a waste of adrenaline.

You enter Armenia into a cluster of grocery stores, kebab shops and roadside guesthouses, making it a natural spot to bunker down for the night. Fresh from a week in Tbilisi the prices seemed cheap too; you can’t go wrong with £1.96 for a chicken kebab**. Trying to work out the ‘real’ cost of everything priced in Armenian Dram bamboozled me at first too, since most transactions run into the thousands (Tip: instead of dividing by 500, multiply by 2 and remove the last 3 decimal places to convert to Sterling).

**fair enough, several things could go wrong with a £1.96 kebab

The Soviet Canyon

Keen to maintain a reasonable distance from the border with Azerbaijan, I followed the road that heads south-west into Armenia towards the town of Alaverdi.

The road meanders alongside the area’s main river, the Debed, which has slowly eaten away the surrounding rock formations to set itself at the base of a deep canyon. Clearly this was an important area of mining activity in the Soviet days: the gorge is littered with the ghostly shells of abandoned industrial buildings, crowned by a (somewhat surreal) abandoned cable car rising out of Alaverdi up to a neighbouring town above the gorge.

There were echoes of my native Teesside’s deindustrialisation in Alaverdi. They have been mining copper in this area since the 18th century, with industrialised extraction expanded under the USSR. I don’t know what sort of state the place was in when the Soviet Union collapsed, but there clearly hasn’t been much in the way of investment since then – much of Alaverdi is like a ghost town.

I amused myself over lunch by watching a local man trying his luck with a spot of fishing along the riverbank. He was getting progressively more agitated by the nearby JCB driver whose unenviable job was to excavate said riverbank. It was all quite Laurel & Hardy; I half expected the fisherman to fall in during a heated exchange, only to be mercifully scooped back onto dry land by his adversary.

Joining Forces

On the way out of Alaverdi I stopped by an austerely stocked local shop and picked up a small plastic cup of Rolls-Royce branded instant coffee with a foil lid (quite a luxury brand to rip-off for such a non-luxury item). It was here I bumped into a blonde haired man dressed in a luminous yellow t-shirt, red shorts and a sunhat…not exactly on trend with the local men’s fashion, he was a cycle tourist of course.

“I saw all of your Ortlieb bags and thought you might be a fellow German!”

Most of the friendliest cycle tourists I have met so far have been Germans, and Jakob was no exception. He had also just ridden and wild camped his way across Turkey to reach the Caucuses – something I plan to do in reverse. Both heading south into Armenia, we agreed to ride together.

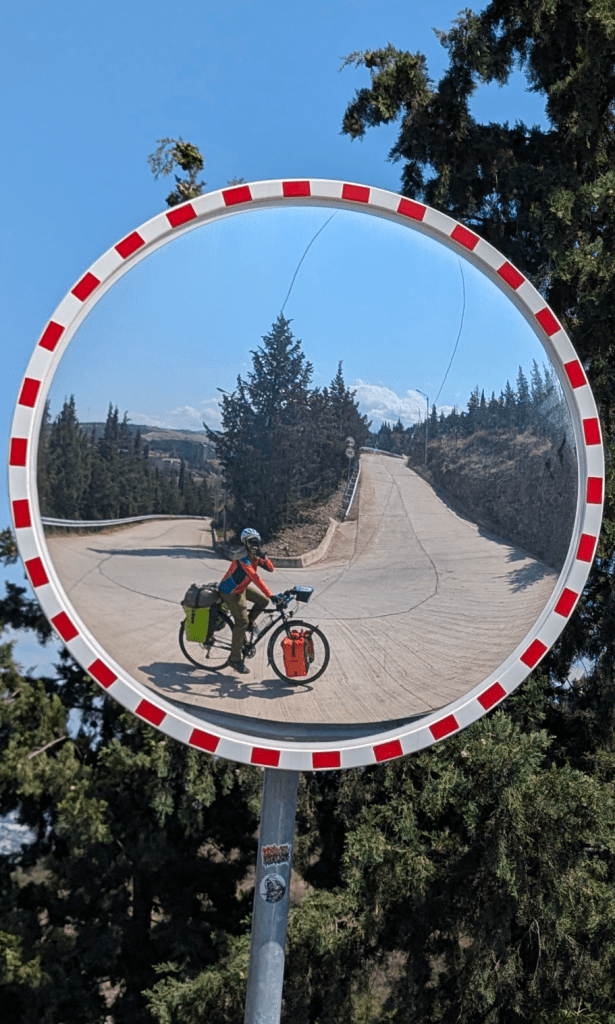

One benefit for the younger and stronger riders who ride with me is they usually dial down the pace, so their legs end up feeling fresher at the end of the day. Meanwhile mine feel just as shot as ever, but I do enjoy the chat between gasps for oxygen at >2,000m in the Armenian highlands.

We were heading to Lake Sevan. This is a seriously big lake – over three times the size of Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland – and about as close as you’ll get to the seaside experience in landlocked Armenia. To get there we would have to negotiate a couple of fairly hefty mountain passes via the popular Dilijan National Park. First though we rode through fading evening light (and an giant swarm of flies on one particular descent) to the small city of Vanadzor, where we bore witness to the spectacle of a man breaking up a fight between rival street dogs using a taser. In his defence I don’t think he actually zapped any of them; the deafening crackle was enough to send dogs scarpering in all directions.

With a family video call lined up I checked into a small B&B with WiFi. Jakob showed his youthful grit and opted to camp at a BMX jump track on the edge of town.

Lake Sevan

As you climb out of Vanadzor heading for Dilijan the countryside becomes increasingly green and lush, with rolling grassy fields sandwiched between densely forested hillsides – a stark change from the more arid terrain that surrounds the Debed gorge.

There are two major descents along this route: down into the town of Dilijan, and then final delivery to the northern shores of Lake Sevan. For us it was a reminder that a strong headwind – annoying as it may be – is preferable to being blasted from the side when going downhill fast.

The Dilijan descent was still great fun, just a bit slower than it would otherwise have been. The ride down to Lake Sevan was another matter: as if the relentless side winds weren’t enough to keep us on our toes, we turned a corner to find the road ahead chock-a-block with cattle. Tempting as it may be to go for that gap between Daisy’s gormless face and Buttercup’s manure splattered arse, sometimes you just have to bite the bullet and grind to a halt on a descent, no matter how much blood, sweat and tears was invested in that momentum.

Like the trucker, the delivery driver, the traffic cop – the cycle tourist spends a great deal of time out there on the road. After a while you come to appreciate a good service station, and the one when you arrive at Lake Sevan is an absolute corker, especially the food hall. You don’t see fresh rainbow trout kebabs on the menu at Hartshead Moor on the M42, you’re lucky if Starbucks has any toasties left.

Our intention was to wild camp along the north shore of Lake Sevan, settling for a BBQ area equipped with metal picnic tables, a haunted looking toilet, and resident dog that would appear from time to time before vanishing back into the darkness like a phantom. So perhaps not the wildest of wild camping, a feeling confirmed by the £5 a night fee we were charged by a couple of impressively drunk site attendants. I was just happy they didn’t want to share our Dilijan lager…we only had a litre between us!

It was here we parted ways. Jakob’s plan was to take the quieter east coast of Lake Sevan and delve into the southern region where Armenia narrows between Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave. I would head for the capital, Yerevan, via the town of Hrazdan to get off the main road…but not before calling by the (imprecisely named) Sevan Island.

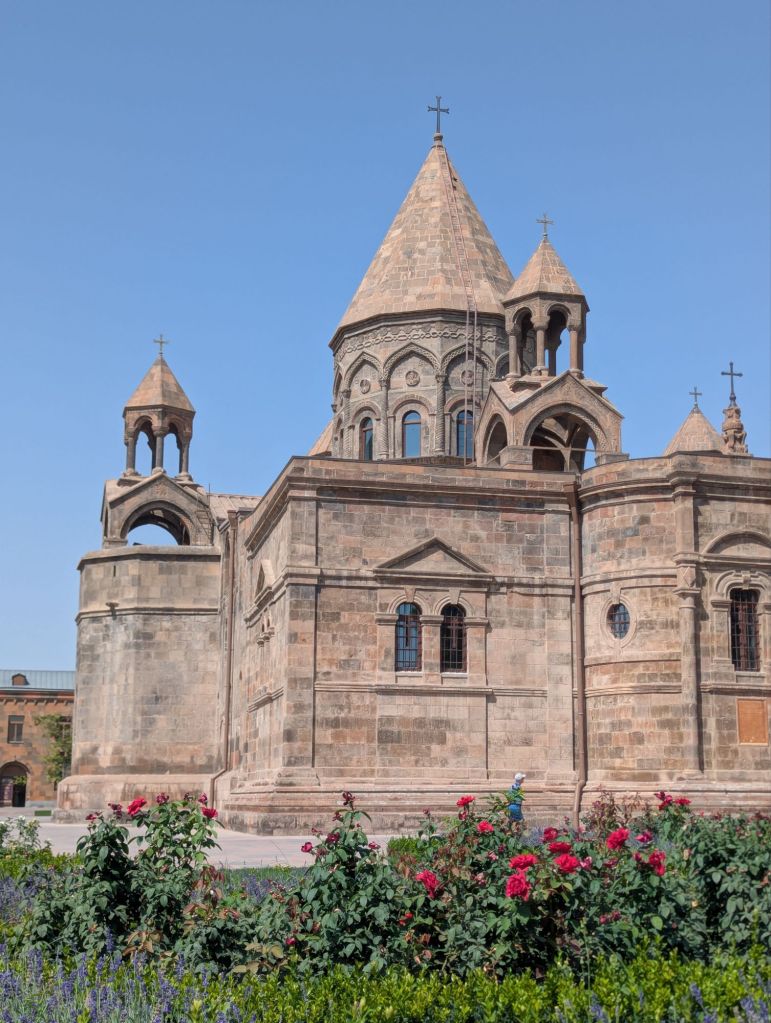

Sevanavank is one of the smallest churches I’ve set foot in. It is also one of the darkest, with barely anything that could be described as a window…perhaps the odd slot in masonry here or there. The main source of light comes from the table where long Caramac coloured beeswax candles lit by worshipers slowly arch over and melt away into the tray of liquid wax. Like in Georgia, it was clear they take their faith seriously in Armenia, certainly when inside the walls of a church.

The road to Yerevan

Of all the countries so far, Armenia is the first where I couldn’t have named the capital city before this trip.

I suppose Baku has the F1, whilst Tbilisi has been more western focused since Soviet independence. Unlike Georgia and Azerbaijan, Armenia is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union along with Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Belarus – so from an economic perspective the Armenians have tended to look more to the east, at least until recently anyway.

If you don’t know much about a country then getting to the capital is a good place to start learning. I also wanted to consult a dentist about the gaping hole in my molar following the Helsinki Filling Disaster of July 2025, a chore I had managed to delay for nearly six weeks.

My route would follow the Hrazdan River as it winds its way from Lake Sevan through a sequence of towns, villages, reservoirs, and a cascade of seven aging hydroelectric power plants, before arriving in Yerevan almost a vertical kilometre closer to sea level.

The road coming out of Sevan city started out perfectly: a freshly laid surface, sparse traffic, and protection from the northerly wind that was beginning to pick up. The shelter wouldn’t last long; I turned a corner onto an exposed stretch of straight road surrounded by vast, empty fields without a hedge or wall in sight. The wind was whipping through a natural gap between the parched, treeless hills before surging down the rounded slopes and hitting me at 90° square.

The sheer weight of my loaded touring bike gives a lot of stability against side wind, but this was just silly. A perfectly consistent wind would be ok – you can just lean into it – but mother nature rarely offers such luxuries. The wind is a chaotic, unpredictable lottery of air flows: brief moments of calm are followed by monster gusts, and you never quite know what’s coming up next. When the big gusts can send you flying into the gutter or under a lorry, it’s probably time to get off and push.

On this occasion the badly exposed section was only around 500m long, so I was quick to hop back in the saddle, and it wasn’t long until the road turned south. The wind that had been trying to kill me was now in my sails.

Stopping for a coffee break in Hrazdan I scanned booking.com for a suitable guesthouse that night, leaving a short ride into the capital the next morning. The small town of Bjini was about the right distance away, and BjiniHouse checked all the right boxes for a B&B – cheap, peaceful location, clean.

Many of the guesthouses in Armenia offer reasonably priced evening meals, BjiniHouse being a particularly good example. Expect fresh salads, meat stews with rice, even grilled rainbow trout (in this case fresh from their own trout farm in the garden), all with big plates of bread on the side so you never finish hungry.

The next morning continued fairly unremarkably until my route turned off the main road just south of Nor Hachn onto the quiet back roads through a relatively undeveloped wedge of land along the river. I ended up on a gravel track that ran alongside a major gas pipeline (operated by Russia’s Gazprom – much of Armenia’s energy infrastructure is Russian owned). There was a variety of dumped rubbish, the occasional angry dog, but virtually no traffic considering how close it brings you to the city centre – maybe the locals knew something I didn’t?

I did encounter one particular hazard along the way, one that had been concerning me as I moved further into Armenia – fire. Wildfires are always a possibility in such arid climates, and I’d previously spotted what appeared to be one in the distant mountains as I rode towards the border from Georgia. Descending into the Hrazdan valley, I glanced ahead and noticed that one side of the road seemed to be much more on fire than usual – the bank was covered in the same dessicated yellow grass that blankets this country in late summer, and it was ablaze.

Looking around me for anything more serious, it was clear the surrounding terrain had been scorched black; the fire had clearly been working its way around the valley. The active burn area was pretty small for this fire, and the heat was quite tolerable from the road, surely this wasn’t Pudding Lane in the Great Fire of Yerevan?

Yerevan

Armenia is mostly quite tolerable in the summer since so much of the country occupies cool high altitude plateaus. That is until you get to Yerevan, where the ‘urban heat island’ effect seems to be turbocharged by the ubiquitous stone masonry. Maybe Aberdeen would feel the same if it was 38°C for weeks on end..

Heat aside, I quite like Yerevan. It’s not as bonkers or edgy as Tbilisi, and apart from having too many cars trying to squeeze their way through the city centre it has a relaxed, laid back atmosphere.

The temporary fillings I had relied on since my amalgam filled molar crumbled in Helsinki were failing to stay in place for much longer than a day. Sifting through the reviews of local dental clinics doesn’t tend to be top of my list when arriving in a new city; Yerevan feels like the sort of place you can find a skilled dentist, but I didn’t fancy having to pull out Google Translate with mouthful of latex gloved fingers and implements, so at least a little bit of English was important too. Despite the occasional scathing 1 star review, I booked an appointment with what seemed to be the expat favourite: Yerevan Dental Clinic.

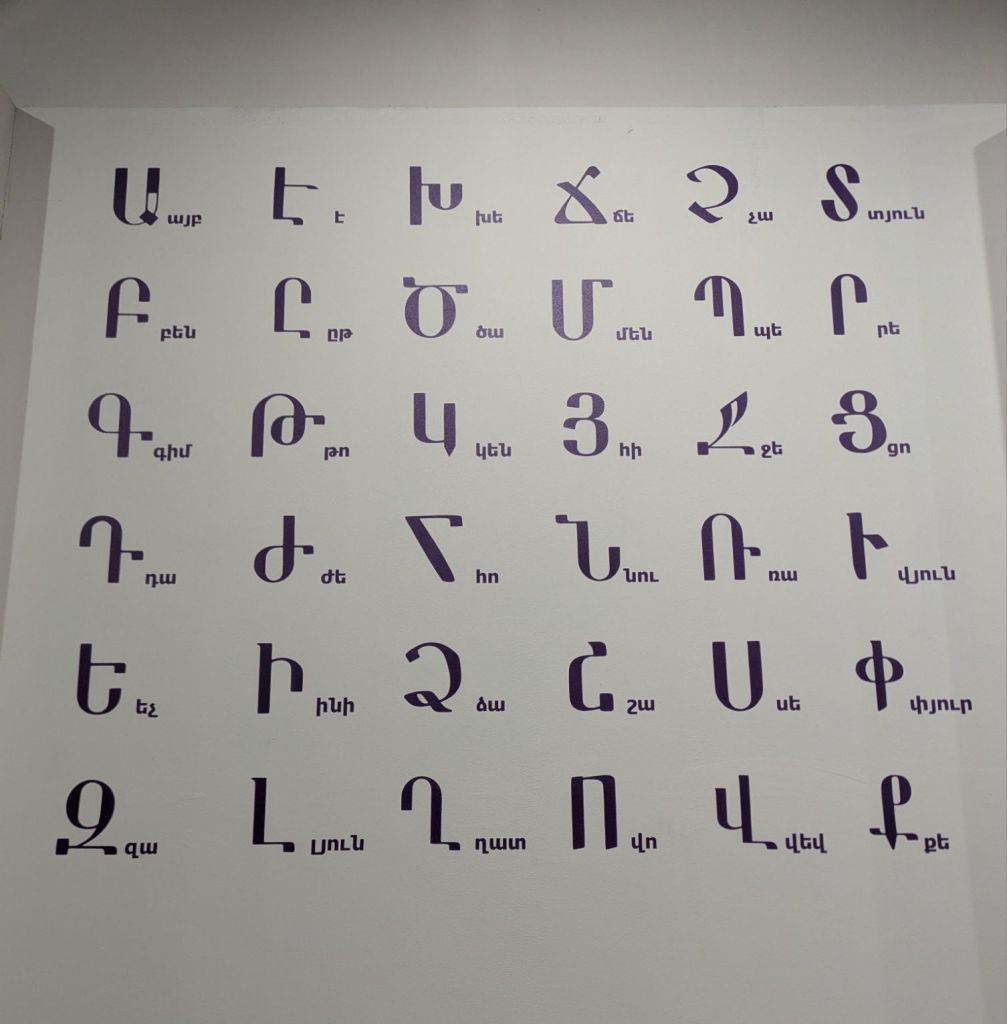

Dental appointment sorted, I could relax, soak up the city and visit a few museums. The History Museum is a pretty good starting point for ignoramuses like me who turn up in Yerevan with almost zero prior knowledge of Armenia. Attempting to summarise the rich history of this country is outside the scope of this blog, but interestingly it was the first country to adopt Christianity as the state religion at the turn of the fourth century.

Outside of the city centre on top of a hill past the abandoned Hrazdan football stadium is the genocide memorial complex. Getting to the museum is quite a long and difficult journey on foot (as I found out on the way there), so it is best to take a taxi or public transport. The complex has its own very informative museum for this tragic but important aspect of Armenia’s history. It is hard to underestimate the impact this event had on the demographics of communities across the Ottoman Empire and what would become the republic of Turkey.

——

My hostel was in a lively corner of the city, and I couldn’t resist popping into The Beatles themed pub around the corner. It was a Friday night and the place was absolutely packed out: not like the Cavern Club in Liverpool with everyone wedged on the dancefloor like sardines in a claustrophobic cellar – this was table service only, with drinks served in a brightly lit mock London pub. It was quite odd, but far from unpleasant. This is no tourist trap though, the locals love it, especially when Hey Jude comes on.

The dental appointment soon came around and I shuffled back into the reclined chair.

“With the size of that hole I’m surprised you don’t have pain!”

It was true: the hole in my tooth was gaping, but it wasn’t painful at all. The plan was to fill the hole with a composite (not the usual amalgam they reach for in Britain ), and it would require a fair bit of drilling, scraping and poking around.

In all honesty I don’t really mind going to the dentist; perhaps I was too relaxed given the man had to keep prodding as I began to drift into sleep, closing my mouth in the process. It did take a long time though, in my defence.

“Wait three hours before solid food”. With that parting instruction (and parting with £40) I was done.

By the next morning I could chew soft food, but anything hard was still a bit sore. Dr Internet reassured me that this was quite normal and I should wait 2-3 weeks. I’m typing this over four weeks in, so what’s the verdict?

Well, it’s good enough for now. The tooth is sensitive to pressure, so anything hard has to be broken down by the primary left gnashers before it can be released for secondary chewing on the right. A mild inconvenience on a cycle tour, but hardly a system to keep up in perpetuity.

Mount Ararat

There was one place I really wanted to visit before leaving Armenia, the Khor Virap monastery that overlooks the iconic Mount Ararat.

Ararat is a dormant volcano standing over 5,000m tall (making it the biggest mountain I’ve ever seen). You can see it from Yerevan on a clear day, but the Khor Virap monastery is a lot closer being more or less on the border with Turkey, about as close as you can get to the mountain without leaving Armenia.

Mount Ararat is a sacred and national symbol to the people of Armenia. It is nowadays located in modern day Turkey (and known as Ağrı Dağı), but that reality has not severed the cultural connection between Ararat and Armenian people. It is on the coat of arms, the brandy, it even crops up as men’s first names. It is said that Noah’s ark ended up perched on the mountain after the Biblical flood waters receded, although it sounded like Genesis was referring to the Armenian Highlands in general…but sometimes you just need a good symbol, and what could be more symbolic than the massive, snow-capped peak of Mount Ararat?

It was here I was reunited with Jakob, who had been on the road ever since we parted ways six days ago. We enjoyed a few beers in the Khor Virap car park café before cycling along a dark, dusty side road and pitched up our tents in a small clearing. Well, I pitched my tent, Jakob has a more lightweight setup resembling a mosquito net coffin. It was a lot more peaceful when the jackals stopped howling and nearby diesel generator got switched off.

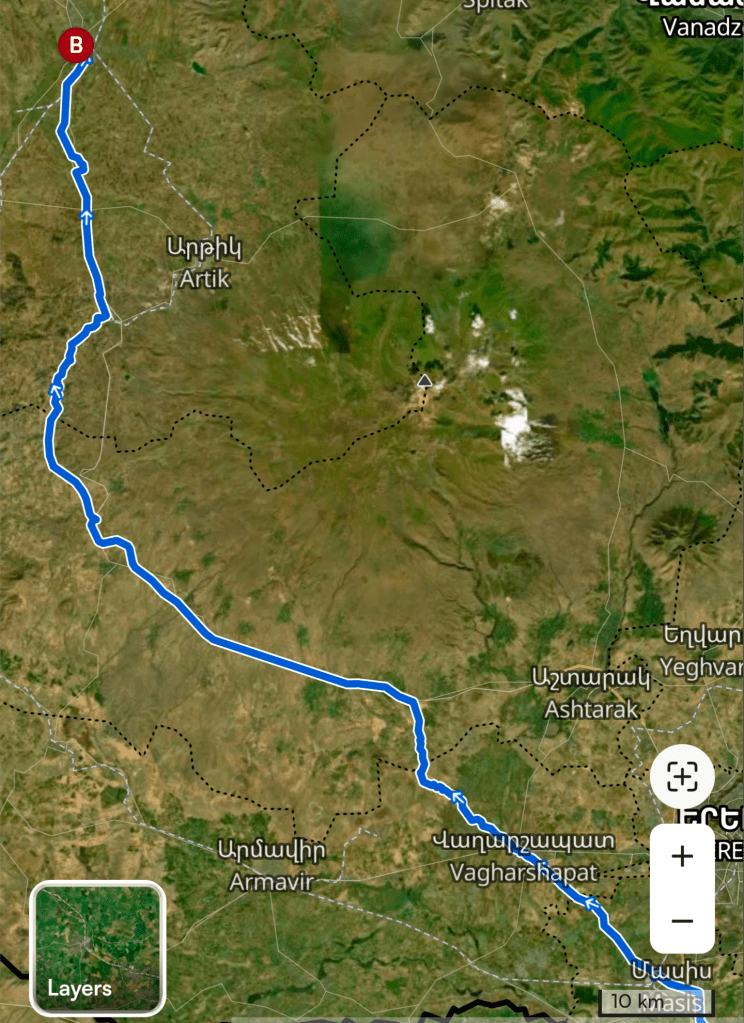

After a short ride back towards Yerevan we parted ways again. Jakob would head into the capital for some well-earned bed rest after a jumbo stint of wild camping had left his sandal wearing feet virtually tattooed under a dense layer of brown Armenian dust. I was heading north for the westernmost border with Georgia, passing through the towns of Vagharshapat and Gyumri.

Vagharshapat (aka Etchmiadzin)

Vagharshapat used to be known as Etchmiadzin, which is worth remembering if you’re easily confused like me. This is where the ancient Etchmiadzin Cathedral is located, often cited as the world’s oldest, although (as usual) the current building has been reconstructed, extended and embellished in various styles over the centuries.

The cathedral sits within a large, peaceful courtyard, adorned with thriving flower beds. Don’t expect a Durham Cathedral style ye olde cathedral experience when you go inside mind you, the interior is maintained to be the immaculate ‘mother church’ of Christianity in Armenia. There are no flaking old frescoes in here.

If you do ever visit Vagharshapat then I encourage you to stay at Machanents House, especially if you’re an art lover. The venue is a social enterprise with small craft shops, art studios, and even a theatre, alongside the restaurant and guest house. Lovely people, cosy environment, and the food is top notch.

The cursed road to Gyumri

The final Armenian city of this trip would be Gyumri, but unsurprisingly for this country there was a 25 mile wide volcano in the way – Mount Aragats (not to be confused with Mount Ararat…keep up!). My route would take me clockwise around the mountain following the main road, but not before taking a shortcut across a gravel track leading to the small town of Aragatsotn.

This is where things began to go a bit pear shaped. As I cycled out of the village of Aragats the houses and farms gave way to derelict buildings, piles of rubbish and an incoherent local drunk wandering around aimlessly. A small white car driving the opposite direction stopped and the driver’s window opened.

“Just to let you know mate, if you go any further down that road you’re going to be arrested by the police.”

Quite the bombshell, and to make things even more strange: delivered in a thick Ozzy accent.

“Arrested for what, exactly?”

“That’s the road to the nuclear power power plant. I should know, they arrested me three years ago and I spent the next four hours being interrogated at the police station!“

So here’s the thing. There was a nuclear power station along the road, but my route went absolutely nowhere near it. If I was creeping around the perimeter fence or flying drones I could understand, but the prospect of being nicked on my route just seemed, absurd.

“I’d turn around and take the main road buddy, all you’ll find up there is my farm.”

I thanked my Ozzy friend (of Armenian heritage) and bid him farewell, then – ignoring his advice – continued on my planned route. In fairness to the guy, he did suggest there wasn’t much along this way and he was right: the tarmac quickly turned to gravel track, which slowly disappeared into the dusty, rocky strewn, dessicated landscape. Before long I was out of the saddle and pushing the bike up steep gradients between jagged, watermelon sized boulders. Every plant that grew seemed to have spikes, spines and prickles just waiting for a chance to bite into my tyres.

Looking towards the hills where my route was heading, I could see a intensively vegetated grid of crops, the dark green standing in stark contrast to the 50 shades of yellow that characterises Armenia’s landscape in late summer. It was surely my Ozzy friend’s farm – if there’s one country that has refined the art of growing industrial scale fruit & veg in this climate, it’s Australia. And I do mean industrial scale, this farm is huge – and located slap bang on top of my route.

My theory is matey was a bit embarrassed to confess his shiny new farm now completely blocked off the old path to Aragatsotn, and that they hadn’t bothered building an alternative path around the perimeter. So instead he spun me the old ‘turn back or you’ll get arrested‘ yarn, that old chestnut!

I wish he’d just fessed up because I would have turned straight back around if I’d known what was in store. It seemed the least horrid route around the farm was to go clockwise, seeking out the path of least resistance across the wild landscape. Within minutes there was a loud crunch and the bike ground to a halt..

A fist-sized rock had been scooped up by a piece of tumble weed that was caught in my spokes, going straight between the wheel and mudguard and crumpling the latter. If it hadn’t been 30°C that day the plastic may well have shattered rather than deformed; I did my best to straighten it all back out and carried on, thankful I hadn’t just been launched over the handlebars face first into a cactus.

At around the half-way mark the farm’s 6ft tall perimeter fence suddenly disappeared and I could get into the farm’s grid-shaped system of internal gravel roads. Realising sneaking back out again would be too much hassle, I simply rode to the main gate, gestured to the security guard I was lost, and exited to freedom before getting tangled in conversation.

Worst. Shortcut. Ever. At least the rest of the journey would be a straightforward main road – and it was, for a while. In the late afternoon a dust-filled headwind picked up, it began to rain, and a distant bolt of lightning lit up the slopes of Mount Aragats. Suddenly, straddling my steel lightning rod of a bike didn’t seem like the best idea, and I waited out the storm under a small concrete shelter and booked into the nearest guest house. By the time the rain subsided my front tyre was flat – the spiky plants had left a parting gift in the form of a slow puncture.

It can really feel like bad luck comes in waves. It doesn’t usually, you just notice it more the rare times that it does bunch up together. But when it does it’s best to try and stay calm to avoid a spiral, because that’s when luck goes out the window and bad decision making takes the wheel.

Gyumri

There’s nothing like arriving at a good guesthouse after a tough day. Maybe it’s partly because I ride solo, but arriving to a veritable feast in the company of jolly landladies and inquisitive cats can really rescue an otherwise rotten day in the saddle. This is the beauty of Armenia, you are rarely far from a good B&B for under £20.

The next morning was spent nursing the bike back to full health before pressing on to Armenia’s second city, Gyumri. Apart from getting utterly drenched in a torrential downpour, it was all rather uneventful.

For me, the story of Gyumri was one of illness. I’d only planned to stay one night then carry on, but a suspicious burger had struck me down with the runs and tanked my energy levels. Rest was the only option, so I bunkered down for two more nights.

The bad luck turned good again when I was feeling better and a fellow cyclist – Eric, an author from Chicago – walked over to say hello. Apparently he spotted me on the highway on the way to Gyumri, and kindly bought lunch at his favourite café, just what I needed after feeling like crap, cheers Eric!

Gyumri is an attractive city with cobbled streets, elegant lamp posts, independent shops…all of which is a lot easier to appreciate without food poisoning.

Armenian Georgia

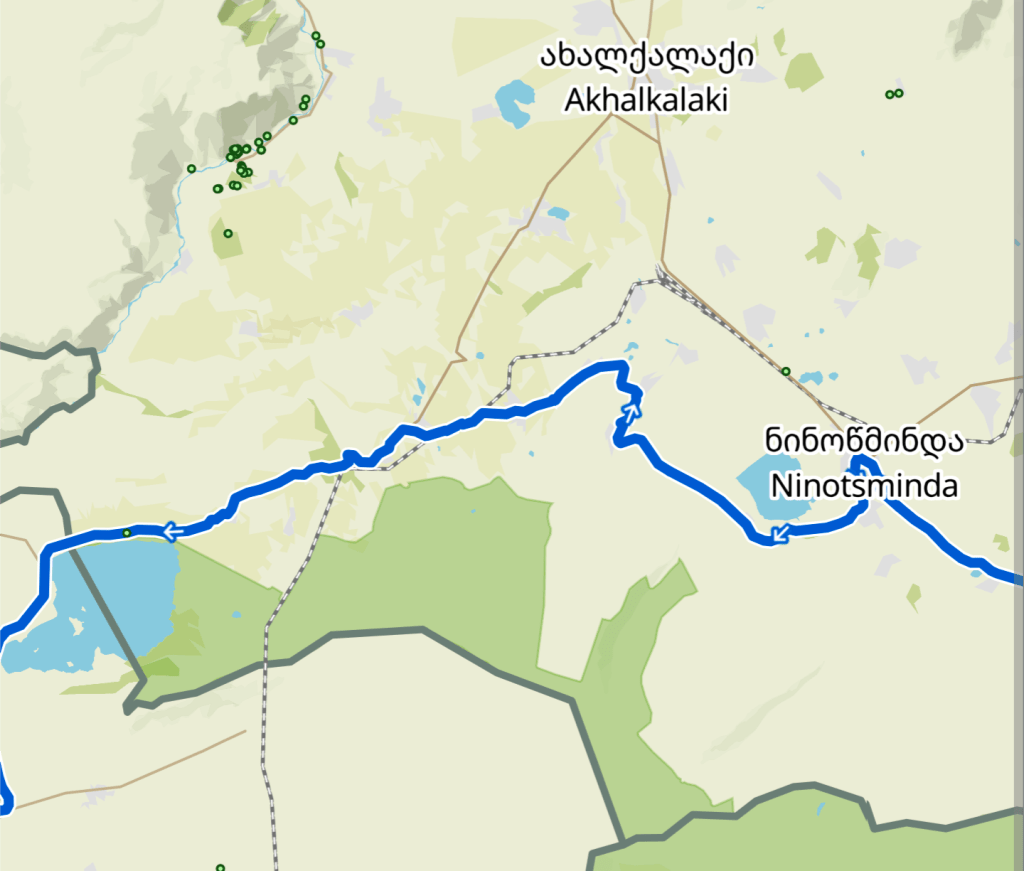

I’m going to close this blog out with my brief journey through Javakheti – the small region of Georgia bordering Armenia and Turkey where the overwhelming majority of residents are ethnic Armenians.

As soon as you cross back into Georgia the Madatapa Lake nature reserve reveals itself on your right hand side, which has an observation hide on stilts along the west shore. Favoured by birds, the lake was occupied by a quite noisy colony of pelicans when I arrived.

I spent the night at a guesthouse in the nearby town of Ninotsminda. One of the fellow guests was an Italian who was shifting his career from travel photography to documentary film making. We hunted down the one restaurant that was still open and dined on kebabs and Georgian beer. Making documentaries didn’t sound easy, but you could see genuine satisfaction in his eyes when he spoke of adding the finishing touches to the project that had been his life for the last year.

———–

I was planning to cross into Turkey at the Lake Aktaş border crossing, where almost every Google Maps review complains about the state of the road on the Georgian side. However it is known to be a quick crossing with not much traffic, and the road should be far better on the Turkish side.

My plan was to cycle along the west shore of Khanchali Lake and follow the back roads through various villages before rejoining the lorries on the main road to the border crossing. I’d heard from several people that the villages in this part of Georgia felt like peering back in time, and I see what they meant.

Some of the agricultural systems in Javakheti were closer to medieval than 21st century. A lady dressed in black was stooped over in a field, piling scythed hay into small stacks with a pitchfork – she must have been in her late 70s, still doing it the same way her own grandmother did. It wasn’t all as manual as that of course, but you got the sense that farming was the main industry here, with lots of small family run farms…there was no sign of self-driving tractors or automated milking parlours out here.

The dirt track I was on taken on a rich red-brown hue and the loose soil contained a few more boulders than is preferable for cycling. I was pushing the bike up a tricky section when I noticed a group of people gathered around a metal shelter at the side of the road ahead. Expecting the usual exchange of barev before continuing on, I was soon ushered to join them in the shelter for a lunchtime feast.

The group was composed of around ten men in their 30s to 50s, who were clearly good friends and in high spirits. Meat was the main course, provided by the lamb being roasted slowly beside the shelter entrance, served alongside fresh bread, smelly cheese (which I managed to dodge), juicy tomatoes, pickles, watermelon and all washed down with a drop of liquor…most were on the vodka, but I went for the iconically Armenian (and slightly less alcoholic) Ararat brandy.

We managed a bit of conversation here and there, sometimes with the help of Google Translate, but I was quite content feasting away and observing the social dynamics around me. At times there were clearly serious matters being discussed, but it was never long before the tension was punctured by roaring laughter. As soon as I finished a plate or glass it was promptly refilled. After 45 minutes or so of feasting, the chap sat next to me (who spoke a bit of English) turned and pointed to the man sat on the end of our bench..

“Singer!”

Music has this tremendous ability to precipitate emotion and activate memories. All the things I had seen and learned about in Armenia started washing around my mind as the man in an Adidas top soared his way through melancholic scales of an Armenian folk song. I didn’t know exactly what he was singing about, but I knew it would be one of the most precious memories I take away from this trip.

As I moved further towards the border there were occasional patches of uncultivated land with warning signs written in Armenian. The country does have a significant landmine legacy from the wars with Azerbaijan, although most of these are in Nagorno-Karabakh, and this was technically in Georgia and nowhere near Azerbaijan. I still have no idea what danger I was being alerted to, but decided to find an alternative spot to have a wee…just in case.

My short journey through Javakheti was capped off with a well-timed invitation for a cup of coffee by a man in the small village of Sulda, which came just as a rain shower was about to unleash. His name was Ararat!

We sat in the corner of the family kitchen. Ararat’s father walked extremely slowly with the help of a stick. His wife was bundling clothes into the washing machine, a chore that would be delayed to get a round of coffee in. His c.15 year old son joined us at the table and asked me a question translated on his phone:

“Why have you come here?”

It’s quite a simple question, but not all that easy to answer. Why had I come here? This time last year I was living a comfortable life as a professional in Shropshire; now I don’t even know where I’ll sleep tonight. I paused for a moment, before typing my reply.

———————–

PHOTOGRAPHY: Armenia

Leave a comment