Salam! This is another bumper edition of the blog, documenting the biggest cultural and climatic shift of the journey so far. If you are a cyclist considering visiting Azerbaijan and have any questions, please feel free to get in touch with a comment or message me directly (e.g. via Instagram).

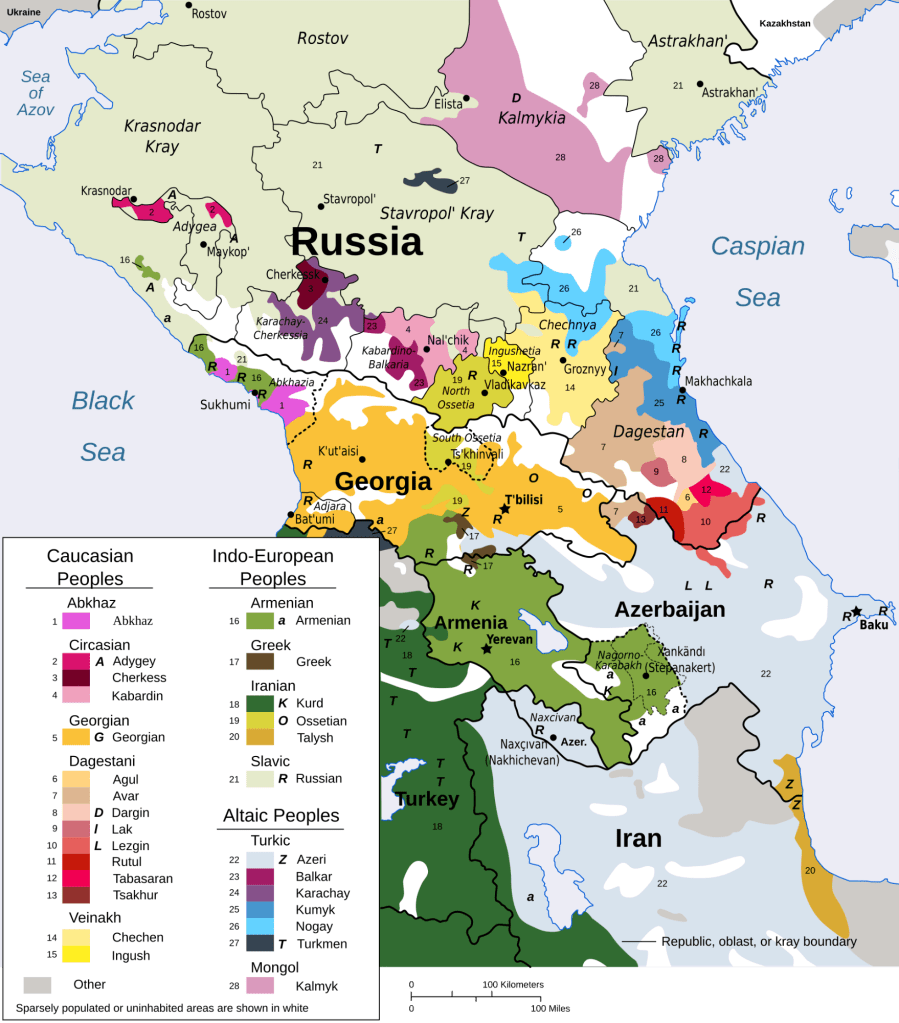

Foreword on the Caucuses

The somewhat fuzzy aim of this journey is to ‘cycle around the continent of Europe‘, making use of various modes of public transport along the way.

So, is Azerbaijan in Europe? Well they compete in the Eurovision song contest (and even won in 2011), but so do Australia – maybe this is not the best metric. Where you draw the outer boundary of Europe is far from an exact science, and there seems to have been all sorts of proposals put forward over the years.

Geology doesn’t offer up a simple solution. Europe and Asia both sit on the same tectonic plate, hence the lack of a nice unambiguous oceanic boundary between the two. But apart from when colouring in the continents on an atlas in primary school, the boundary is ultimately, fairly meaningless. It’s the boundaries of nation states, rather than continents, that have material consequences, especially when differences of opinion arise.

The Caucuses are a bit like Eurasia’s central junction, a mountainous intersection between worlds. Their inhabitants have endured invasions from all directions over the centuries – the Mongol, Persian, Ottoman, and Russian empires to name a few – with the republics of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia emerging as sovereign states following the collapse of the Soviet Union. There exist long-standing territorial disputes amongst the region’s diverse ethnic groups, at times escalating into all out warfare – something I would be frequently reminded of when travelling across Azerbaijan.

Looking at the map, it was starting to dawn on me how far east I had manoeuvred. Baku is east of Moscow, Syria, Ukraine, Iraq, Kuwait, and every country in mainland Africa except the pointy end of Somalia. Then there’s the heat, with forecasts hovering around 39°C in the late afternoon – that is just cruel.

With my bicycle successfully re-constructed in Heydar Aliyev Airport car park, it was time to start meandering my way in the only direction that didn’t lead straight into the Caspian Sea: west, towards home.

Escape from Baku Airport

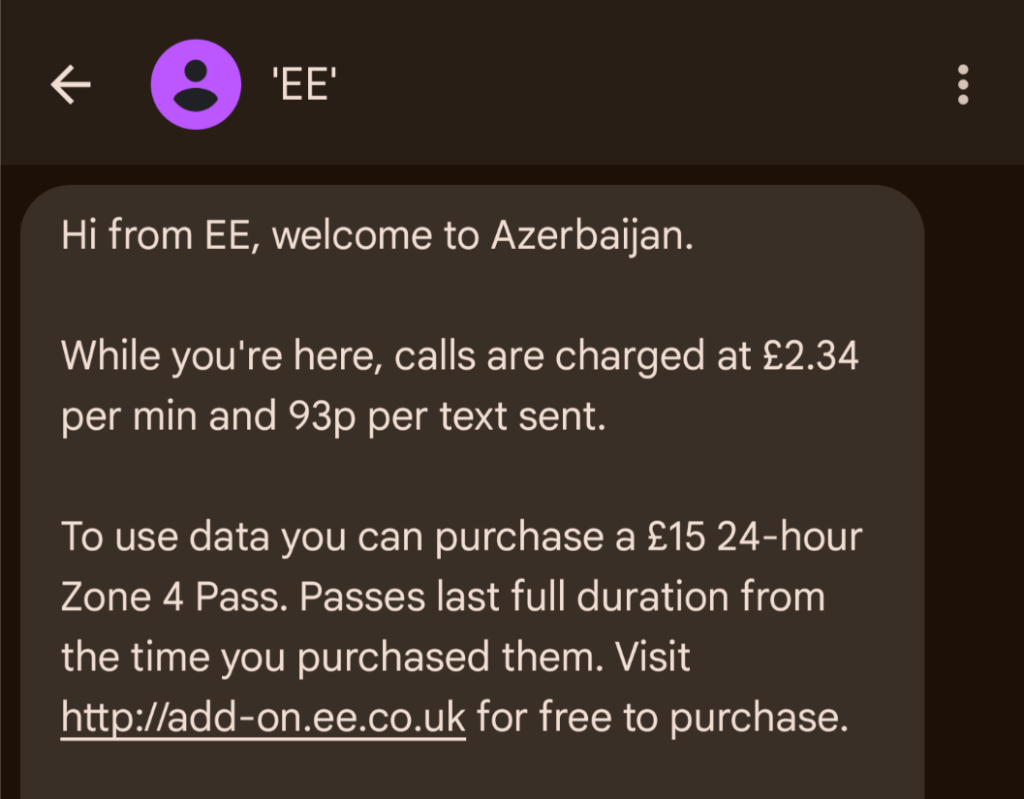

It’s amazing how dependent you can become on technology when traveling. I use my smartphone for all sorts when out and about, but especially for navigation and translation. Upon landing in Baku I received this slightly tepid welcome message from my mobile provider, EE.

EE’s generous offer is you can pay £15 a day to continue using your data plan, which equates to around £450 a month…eye gougingly pricey. What I needed was to install an ‘eSIM’ to get mobile data at a fair price, but having never installed one before I could feel it in my bones the process wouldn’t be straightforward – I just wasn’t in the mood for mucking about with tech problems, I wanted to get to my Airbnb in Baku’s Old Town and sort it all out there. So I logged onto the airport WiFi, looked for the key roads I should be heading for on Google Maps, drank an iced coffee, and headed for the airport exit.

In cycling your way out of Heydar Aliyev Airport it doesn’t take long to realise that cycling safety was probably not a high priority in the transport network design matrix. I had to cross six lanes of traffic just to get out of the place, and there was absolutely no way I’d be cycling on the traffic saturated mega-motorway into Baku. Mercifully, there was a concrete path running alongside the highway, or at least to begin with there was.

My route into the centre of Baku could probably be best described as ‘indirect’. Less as the crow flies, more like a hedgehog sniffing its way around the garden to find a suitable hole in the fence. A common design feature of Baku neighbourhoods is the absence of a through road – many districts seem to have only a few key roads leading in and out – so I kept finding myself going around in circles looking for an exit, usually to the bemused looks of local men as they sat smoking cigarettes under the shade of trees.

It felt like a milestone getting away from the motorway and into residential districts, but this came with its own hazards. Slippery patches of a mystery liquid leeched onto the road from roadside markets, occasionally flowing into open drainage channels that could be two feet deep. Potholes are a constant threat especially on downhill sections, and the constant coming & going means you really have to be on your guard to avoid a dreaded car door encounter.

There were a few roads that felt just a bit too busy, fast and narrow for my state of mind, where I opted to push the bike on the pavement instead. Normally this is a slow but easy option, but in Baku the kerbs are rarely dropped and often rise 12+ inches high meaning you have to actively lift up the bike to avoid the sound of chain ring grinding on concrete – repeat this lift manoeuvre every time you pass a driveway in a residential area and, suddenly, riding along that busy road doesn’t look like such a bad option after all?

After some painfully slow progress where I (barely) pushed the bike up the world’s steepest footpath only to spend the next hour going in the wrong direction and having to retrace my steps, I finally got myself heading towards town on the gloriously straight Babak Avenue. This is by all accounts a busy road, but it is flanked by a bus lane for the most part, which most of the cars stay out of, and as a safer alternative there’s often a nice wide footpath or side access road you can ride along instead. The road is also home to an endless supply of car show rooms and spare parts merchants, clearly there is plenty of demand: in my left ear there was a piercingly loud tyre screech and BANG – a black saloon had been rear ended by an SUV.

It was all quite straightforward from Babak Avenue. I stopped at plenty of supermarkets for refreshments, shopping at a leisurely pace in the air conditioned aisles. I may have survived Day 1, but clearly I would need some specific hot weather clothing going forwards.

Adjusting to Baku life

My ride into Baku gave me a brief peek inside the ‘real’ Azerbaijan well outside the orbit of souvenir shops and tour guide sales reps touting for business. Not to take away from central Baku and its blend of historic and ultra modern buildings, it’s just that 99% of Azerbaijan isn’t furnished with neo-futuristic buildings designed by Zaha Hadid, triple sky scrapers shaped like burning flames, or public gardens with mock Venetian boat rides.

I spent four days in the city altogether, plenty of time to recover from the flight, ease myself into the hot climate, and drill a few elementary Azerbaijani phrases into my monolingual skull. You don’t have to walk far out of Baku city centre before the English speaking drops rapidly, especially amongst older folk who learned Russian under the USSR.

Inside Baku’s Old City walls is a well preserved labyrinth of narrow pedestrian streets. It is quite fun to just wander aimlessly through the maze and see where you end up, usually at a souvenir carpet shop but occasionally an ancient palace or tower. The city is home to a healthy population of street cats, who I was a bit cautious of at first, until realising their default mode is to ignore your very existence – better to be shunned than scratched.

The population of cats that roam the streets of Baku is exceeded only by that of police officers. In fairness Baku feels like a safe city in terms of street crime and the police presence probably helps in this regard, but it’s hard not to wonder what some of them actually do all day other than cruise around in flashy patrol cars at excessive speeds with the beacons flashing. Actually, I do know, occasionally they remind tourists to not take photos of cats sleeping on the steps leading up to government buildings (I’m unsure what the security risk was supposed to be exactly, but I sensed this wasn’t a moment for debate).

An online search led me to a couple of small outdoor clothing shops just beyond the city walls. They were more hiking than cycling focused but that didn’t matter, they had clothing to survive in hot weather: loose-fitting thin trousers, a long sleeved jersey, and a (faintly absurd looking) cap equipped with UV rated neck flaps.

Catching a bus from Baku to Lankaran

I was curious to visit the mountain communities in southern Azerbaijan, which would take me about as close as possible to Iran without actually crossing the border and waving goodbye to my travel insurance (yes I could probably get a separate policy to cover Iran, but I doubt a certificate of insurance is much help when you’re banged up in a Tehran prison on fabricated espionage charges). The Talysh Mountains also looked quite green and lush on the satellite image, so perhaps a bit more cool and fresh than bone-dry Baku.

The coastal road heading out of Baku never seemed very appealing to me, so my plan was to get a bus down to the city of Lankaran and cycle across the country, exiting at the Lagodekhi border crossing into Georgia.

The bus is very cheap and you can purchase tickets using the Biletim app. If you have a bicycle I recommend choosing one of the larger coaches (you can see how big the vehicles are by the seating plan) and make sure you give yourself A LOT of time to get to the bus station, it is an absolute pig of a journey by bicycle. Even once you arrive it can take a long time to figure out where your stand is.

I was so bamboozled by the bus station layout I ended up having to catch a later departure, not a big deal though given you can cancel tickets on the app for a small fee. Around 30 minutes before departure the driver opened up the luggage compartment and gave me a hand loading my bike and panniers inside. There is no formal fee for bicycles, but I gave the driver a 5 Manat tip (around 75% of the fare) since he helped me out and the ticket only cost around £3.50.

I honestly don’t know if it would be possible to get the bike on one of the smaller buses, but the coach was convenient and reasonably comfortable. The driver’s mate handed out free cartons of water which felt like being back on a school trip, and we stopped at a service station to stretch the legs and top up on snacks.

If you do visit Lankaran by bus I can highly recommend the Xan Lənkəran Hotel. It was under £25 a night and just feels really cosy inside with all the solid wood fixtures, friendly staff and a decent restaurant…plus you only have to walk 20 metres from the bus stop!

Lerik – the town on a mountain

After a tasty meal that made the palms of my hands and soles of my feet itch (this is walnut country, luckily my allergy is fairly mild these days) I logged into Komoot to plan a route from Lankaran to the towns of Lerik and Yardimli. I was keen to get off the main road where possible, so I pieced together a circuitous route of unpaved gravel tracks linking the surrounding villages.

The road through Lankaran was buzzing with commercial activity. You can walk into a furniture store to collect your shiny new glass dining room table, cross the street and pick up a whole sheep (dead or alive). One vendor ambitiously tried to sell me a slaughtered lamb, not exactly the most convenient cycle touring food option; I politely declined.

The R48 road linking Lankaran to Lerik gets quieter once you cross the motorway junction, but there are still plenty of cars and the odd lorry. The road is fairly wide and rarely steep, so as far as main roads go the riding isn’t bad. After an hour or so I took a left at the village of Piran and swapped tarmac for some rather dusty looking gravel.

The dirt tracks were ok at first; my legs were still fresh and the surface was uneven but rideable. It was a short honeymoon though, before long my back wheel began to lose traction on the deep sandy sections, and there were some brutally steep ramps where I simply had to get off and push. To make matters worse, for some reason I was wearing my civilian red suede shoes (don’t ask) which just slid across the loose gravel, getting me nowhere. At least I could actually push the bike when I swapped back into suitable footwear: the question was, how often would I need to?

My reward for this hard work was a downhill section that brought me alongside a small stream, which had been few and far between so far. Spotting a café sign pointing to a nearby property, it seemed like a good time to stop and cool down, even if I’d barely made a dent in the planned route to Lerik.

Fair play to the family who run this café. You come in for a cup of tea, and before you know it they’ve sold you an off-road tour in a Lada 4×4 to a waterfall 10km up the mountain. I was mildly concerned it was some kind of scam at first – and wondered if the chainsaw my driver loaded into the boot was for sawing through logs or bones – but the warmth exuded by the family felt too genuine. The waterfall was clearly a tourist hotspot for locals, and my little excursion included more chai and lunch with an older couple who were based at a shack next to the waterfall carpark. The chainsaw was for cutting firewood for the wood burning stove, thank God.

I ended up spending most the afternoon on this little detour. When I returned a group of young men in their 20s turned up for a round of tea, insisting I join them for a few cups. They reminded me of my friends at that more care-free age when life seemed to be more simple. There is more wisdom and self acceptance in your 30s, but it can be harder to corral a big group of friends together for a cup of your favourite brew.

My hosts confirmed my suspicions that it would be a very bad idea to try and cycle to Lerik following the back roads. I turned around and headed back from where I had came, onto the asphalt of road R48.

As the evening set in I could see the faint twinkling of lights on a hill in the distance. I knew that this must be Lerik, but my brain was failing to comprehend the magnitude of what I was looking at. Evening turned into night, and around 5km outside the town walls I detected red & blue lights flashing in my peripheral vision, followed by a brief siren instructing me to pull over. I had passed dozens of cops all day without issue, but for some reason these chaps pulled me over – they were friendly enough and mainly just wanted to check my passport. They didn’t stop me for that long in fairness, but it was starting to get late and I had no accommodation lined up.

I failed to find any hotels that could be booked online or that even had a phone number. The address of Hotel Lerik on Google Maps brought me to the Ministry of Finance (helpful!), so I placed my faith in a group of enthusiastic young boys, the eldest of whom spoke impressively good English. After wandering the streets for 20 minutes we eventually found Hotel Lerik – it was closed. I decided to cut my losses and camp in the woods.

I pulled up at the side of the road to inspect a patch of land where I could camp for the night, only to be accosted by another police passing police officer. This one was working solo and seemed more grumpy than the last duo, insisting to inspect my bags for any dubious materials. I explained my predicament and he recommended another hotel which I was certain was full (it was on booking.com but showed no rooms available).

I don’t know if it was a language barrier or he just didn’t want me to camp for some reason, but he insisted I go to this other hotel. I agreed to give it a try: it was full, and I was fed up. Given that in some sense I was following police orders, I just setup the airbed & sleeping bag on the hotel’s outdoor patio and fell asleep to the chorus of Lerik’s amateur canine choir.

Lerik to Yardimli, the short way?

To get to Yardimli from Lerik you could descend all the way back to Lankaran, take a relatively flat road up to Masalli and hang a left onto the main road up to Yardimli. But that would be 140km, why drag it out when you can just ride the 45km driving route advised by Google Maps?

In fairness I did see a few cars along this route, so you can technically drive it, but be warned: with 20/20 hindsight, I do not recommend this route on a heavy touring bicycle.

It was a glorious morning, and the benefit of sleeping on a porch was that I was up and away by 5:45am, with the cool morning air and a stunning sunrise. Much of the first 15km or so was downhill which was great where the road surface was still intact, less so on the bumpy subbase.

The high-pitched drone of insects was in constant surround sound up in the mountains. Maybe it was the grasshopper/ cricket creatures that jumped in all directions when I wandered onto the verge to take a photo? It was a stunning landscape, but away from the forested areas the land was looking extremely dry. I just prayed nobody was going to toss a smouldering cigarette butt out a car window – the grassy areas looked like they would light up in a flash.

There were at least two occasions where upon the sounding of a deep, throaty “woof”, I looked up to see a large, angry looking Kangal Shepherd Dog on the roadside up ahead. Some of these dogs are truly enormous, much bigger (and slower) than Border Collies, and I did not fancy taking a bite from one if possible. As it happens, there was a recurring pattern that emerged: they stand and bark, then as you get near they begin to chase – keeping the speed down so they never quite catch you – following until you pass the property and their job is done. You could get bitten but it’s quite unlikely; I mainly just try to avoid direct eye contact and ignore them. If they appear on a steep climb I sometimes opt to push instead since they don’t tend to harbour the same grudge against pedestrians.

After a few hours I rolled into a village large enough to sustain a small shop where I shovelled down an 8:30am ice cream. I always greet the people I come across with a “salam”, including on this occasion two men sat outside of the shop entrance. One of them asked if I would like a cup of “çay” tea, showing me around the corner to where the serious tea drinking takes place.

Next to the shop were several long tables and a dozen chairs, arranged so that those seated could look out towards the road and watch their little corner of the world go by. They seemed to know exactly who every single person was who drove past, with most cars stopping to stock up on freshly baked bread and often joining the çay session. In Azerbaijan they have a saying:

“Çay nədir, say nədir”

I’m told it translates to something like ‘no amount of tea is enough’. I had four cups, which felt like a lot in one sitting, and they even plied me with bread and cheese, refusing to accept any money in return. I can see how easy it would be to let the hours pass by sitting in that shaded corner of the village, watching the charcoal fire crackle as another pot of tea came to the boil, but I wanted to reach Yardimli by lunchtime and put my feet up after a night on the patio.

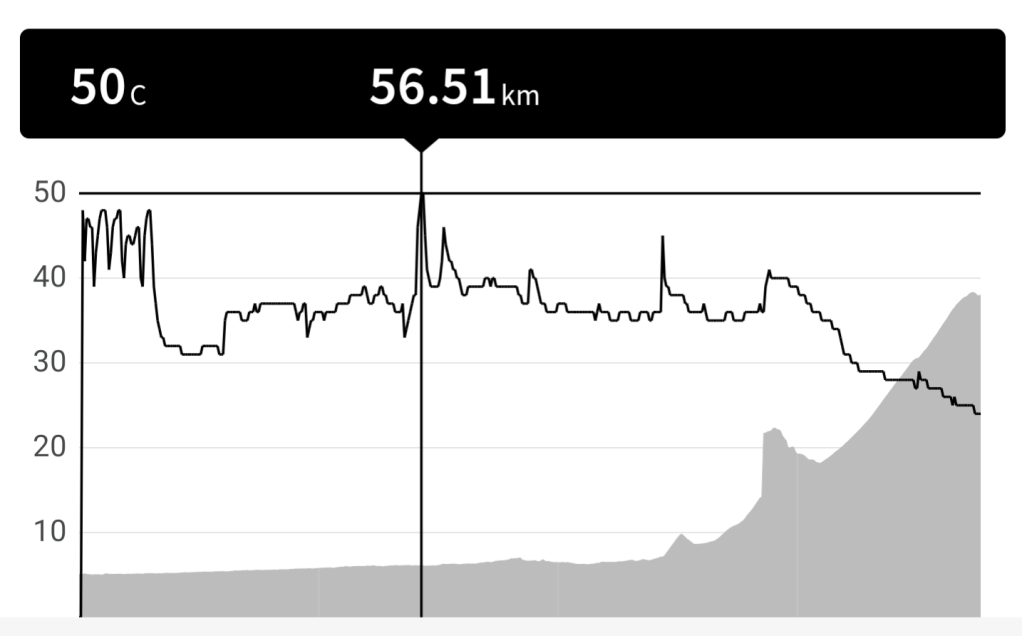

This is where the route became challenging. I descended into a small village where one of the locals pointed out the road to Yardimli. I rode right past it the first time around, resembling more of a stony walking path than a road – I was about to head back onto gravel, and it was getting seriously hot. As usual, it started off ok where the path ran adjacent to a dried river bed, but then it all changed. The path rose up into what would be one of the most unpleasant climbs I’ve ever attempted with a bicycle. I say ‘with’, because I was rarely ‘on’ the bike for this section, it was just too steep, too sandy. Discounting the ride into Lerik the day before, this would be the biggest climb I’ve ever done in my life – and I’ve ridden up some good size mountains before!

The difficulty was amplified by a lack of shaded rest places. Sometimes I would have to dump the bike and walk down the hill to a lone tree where I could shelter for five minutes, it may not sound like much but these short breaks make a huge difference. The hat was a life saver, I may have spontaneously combusted if the sun was on my neck and face that day.

But all hills have a summit. The road surface returned to tarmac and I reached another small store where the kind shopkeeper gave me tissues to clean the sweat from my face. After 7.5 hours since my departure I reached the Arena Hotel in Yardimli by 2:30pm: it was the hardest 45km of my entire life.

Traversing the Iranian borderlands

I basked in the comfort of my air conditioned hotel room in Yardimli. The hotel was part of a modern sports complex with Olympic rings plastered on the front. I couldn’t recall the Yardimli summer games, probably because they never happened – it is one of a network of ‘Olympic’ government funded sports centres built since the year 2000 to provide access to decent quality facilities in the provinces, and most of them have a reasonably priced hotel attached.

—-Driving in Azerbaijan —-

The hotel manager had offered me a lift to the local supermarket so I could stock up before my departure. A Russian gymnastics coach who was working with the Azeri team was in the front passenger seat, so I climbed into the back and began to try and release the seatbelt which was trapped under the seat.

“No no no, don’t worry – you don’t need those in Azerbaijan!” my driver reassured me, as if my main concern was being told off by a traffic cop for not wearing one.

“Well promise me you won’t crash!”. Good job our shop was only around the corner.

The standard of driving in Azerbaijan was an eye opener. They drive fast and loose, and don’t always let inconvenient things like rules of the road or speed limits hold them back. There is no shortage hazards out there on the road – potholes, drainage channels, cows, pedestrians, cars manoeuvring without indicating – so expect a certain amount of swerving on your way from A to B. My Yardimli friends would probably think I was the squarest of squares if they saw me drive, and I’m perfectly happy with that.

—————-

My planned route would send me down the main road out of Yardimli, only to hang a left and go straight back up another chunky climb. I was fine with this on the condition it was tarmac – and the aerial photography suggested it was – so I stuck with the plan and headed for a road that would take me to within a few hundred metres of Iranian soil.

There was no early bird 5am rise this time. Nope, I set off at noon, fully rested but straight into heat. It was a strategy I would continue across Azerbaijan: ride in the heat, then rest in a hotel where I could have a shower, wash my riding clothes, and get a good night’s sleep. Ride hard, rest hard. In many ways it worked well, but mistakes were made too..

I found myself weaving between molten sections of road, hoping the black liquid wouldn’t eat into my tyre when I inevitably veered into it. It was clearly a hot day, but it didn’t help that the bitumen was freshly laid. After passing through several eerily quiet villages I reached the summit plateau and got my first glimpses across the border.

I can’t say the snippets of Iran I managed to peep into looked all that different from Azerbaijan, other than maybe the fields being slightly different shapes. Would it feel like a completely different country if I rode through a town on the Iranian side? The area was historically known as Iranian Azerbaijan after all, largely inhabited by ethnic Azeris, but the systems of governance have diverged radically since each side of the border was all part of Persia in the early 19th century. Maybe one day I will find out, just not on this trip.

The mountain descent was hampered slightly by an unrelenting headwind, but I was just happy to have a breeze on my skin. The ambient temperature was slowly rising as I lost altitude, and I stopped at one of the roadside drinking fountains to rehydrate.

Azerbaijan has a network of public drinking water stations at the roadsides, often on remote stretches of road where there are no nearby shops. They’re easy to find since they are invariably housed within shrines dedicated to Azerbaijani soldiers killed in conflicts over the long disputed Karabakh territory, usually with a prominent photograph accompanied by the Azeri and Turkish flags. As it happens, I actually met two war veterans in this particular shrine who I had bumped into previously on the road. They seemed like genuinely nice guys even if they did try the ‘would you like to swap mobile phones‘ trick. They were clearly very proud of their military associations, and maybe they knew some of the people the shrines were in memory of, the war was only a few years ago after all.

Personally I always filter this water – as I did with all tap water in Azerbaijan – but you might want to consider disinfecting for viruses too if you’re being careful. Thankfully I never got a case of the green apple splatters, but the water tasted pretty unpleasant to be honest, usually quite salty, and I would be wary about consuming such tap water for a prolonged period. A lot of people still rely on bottled water in Azerbaijan for their primary consumption and most shops sell whopping 19 litre bottles to service the demand. I struggle to wrap my head around how an oil rich country can have such poor drinking water provision outside of the capital, but maybe I’m just being naive?

The mountain communities up here are a long way from any major urban centres and sometimes look like they operate in ways unchanged for hundreds of years, living off of the land and utilising local materials. It is a stripped back, traditional way of living, but it never looked like an especially poor quality of life, not at least from my superficial perspective.

Heating up in Azerbaijan’s pan-flat centre

Going fast downhill on a bicycle is always refreshing on a hot day, until you reach the bottom that is and the A/C gets switched off. The centre of Azerbaijan is remarkable in its flatness, and the air masses seem to just sit there, creeping up in temperature until they approach roasting-point at around 5pm each day. This place is absolutely baking in mid-summer, and it was about to kick my arse (in a more literal sense than you might have bargained for when you started reading this blog).

One good thing about leaving the mountains was I was back onto consistent tarmac, despite the best efforts of my GPS trying to take me back off again. This was a recurring theme – the route I had mapped out from the comfort of my hotel room would often take ‘shortcuts’ along unpaved roads.

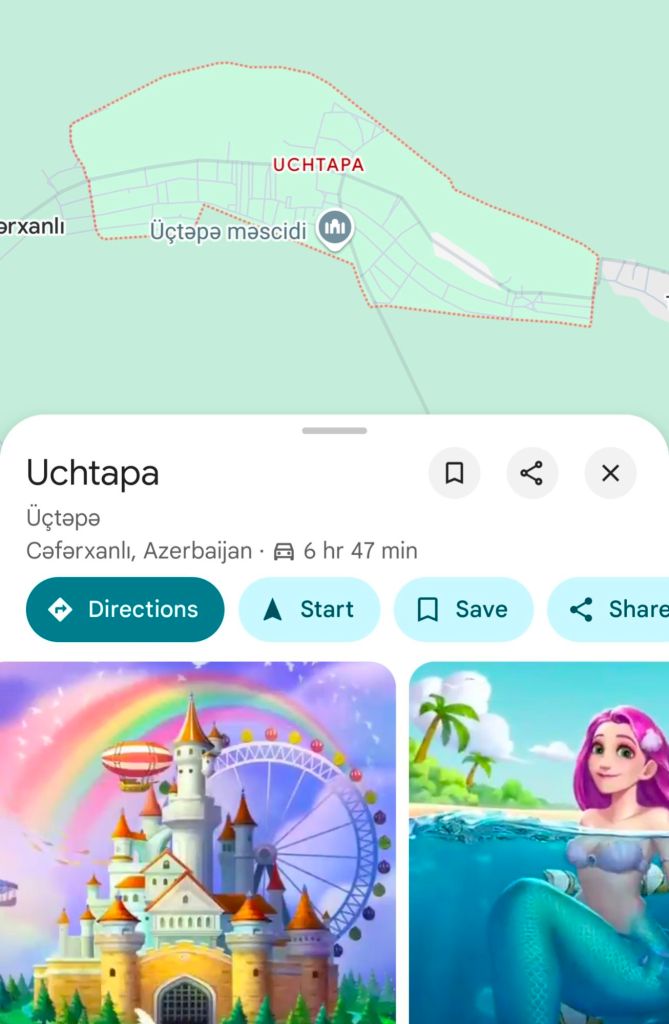

I rolled into the small town of Üçtəpə (Uchtapa), where halfway through my planned route diverted off the main thoroughfare onto a gravel track that led into the vast expanse of agricultural land surrounding the town towards the city of Bilasuvar.

Üçtəpə was my realisation that there is real poverty in 2025 Azerbaijan. It was the first time I’d seen open sewers along the road, or ridden through plumes of toxic fumes from piles of burning rubbish whilst children played games in the street. It felt different to the mountains, the environmental problems exacerbated by a higher density of residents. I don’t know if Üçtəpə technically qualifies as a shanty town or not, but it is the closest thing I have seen to the images conjured up by that phrase.

Just to be clear, I am not seeking to slight the town or its residents, I just want readers to know that – like many places – the wealth in Azerbaijan is unevenly distributed, and this inequality can be quite extreme in places. I stopped right in the centre of Üçtəpə to double check my navigation, where I was immediately mobbed – first by the curious local children, followed quickly by the more skeptical adults. A broad, muscle bound gentleman of substantial mass who seemed to be a ‘man of local influence’ walked over to me, so I shook his hand and repeated my usual spiel of how I was cycling to Istanbul. He didn’t seem overly impressed, and it was suggested to me by one of the children that now might be a good time to leave; I took the child’s advice and followed the main road to Bilasuvar.

The next few days blur into one in my memory. I made my way across the country following the longest and straightest roads of the tour to date, they put Finland to shame out here! I could be riding for 30 minutes and see nothing but a few spiky shrubs and a telegraph pole for shade.

I thought I was drinking plenty of fluids but with hindsight, perhaps not enough. I also didn’t use hydration tabs too to keep my electrolytes in balance (which you can easily purchase from chemists), so that’s something I would change next time around. By the time I reached İmişli my belly was beginning to feel bloated and my energy levels were down. My digestive system had gone into water conservation mode, and it was becoming difficult to ‘pass solids’ on the toilet. This culminated in a minor (but nonetheless unpleasant) internal tissue tear and the oh so pleasant symptom of ‘bloody stools‘. So please, learn from my mistakes people and STAY HYDRATED IN HOT WEATHER, your arse will thank you for it.

Looking at the temperature chart above (recorded by my GPS), the 50°C temperature spike was probably from parking the bike in the sun on a lunch break, but you get the idea – daily temperatures could fluctuate between fairly hot and full incineration.

Digestive woes put to one side, there were some things I got right. I took regular breaks (ideally in the shade, but sometimes just using my headgear for shelter), and stopping for cold orange juice and a 40p ice cream at village shops became a sacred cool down ritual, where the shopkeeper might hand me a tissue to wipe the sweat, dirt and salt crystals from my brow.

There was no wild camping for me in Azerbaijan. It was just too hot, too sweaty, and apart from in the mountains there weren’t all that many places tempting me to get out the tent. Since Azerbaijan doesn’t have formal campsites, one option might have been to ask the restaurants and tea houses with enclosed gardens if I could camp for the night, away from the roaming street dogs – the chances are they might suggest to stay in their house instead.

Since I was staying at the local hotel instead, there was always a moment of jeopardy as the receptionist showed me to my room – would it come with my very own Persian-rug equipped living room (Zardab), or would it resemble a 32°C squat where the only running water was from the bidet (İmişli)? I had a bit of everything, but they were mostly fine, A/C equipped and never more than £25 a night. Importantly they gave my body a little haven to recover from the extreme heat of the day, so I started each day well-recovered.

Sheki and the border crossing

Zardab to Sheki was my final major ride in Azerbaijan, and for some reason I decided to do it all in one day rather than the more sensible option of two. I knew it would be longer than my other rides, but Sheki is located up in the foothills of the Greater Caucuses, so there would be a hefty climb before reaching my guesthouse.

It was ambitious and inevitably resulted in a late (10pm) arrival, but I was just glad to be staying somewhere up in the hills and out of the baking hot flatlands. My guesthouse didn’t even have air conditioning, but with cool evening air and fly nets on the windows, it didn’t matter.

Sheki was the perfect place to spend a couple of days and recover after the exertions of crossing the country. My guesthouse – Ilgar’s Hostel – is listed as a homestay, and it was one of the most peaceful environments I have ever taken lodging. The lady who made me breakfast and cups of tea throughout the day was the epitome of calm, and could often be found tending to the house’s flourishing rose and vegetable garden.

Sheki was a prominent town on the Silk Road and it was the first town I had seen tourists in Azerbaijan since leaving Baku, where they come to visit the well preserved old town with its caravanserai and the impressive frescoes and stained glass of the Palace of the Shaki Khans.

I was ending Azerbaijan on a high. I flirted with staying in the country for one more evening until I discovered the main hotel in Balakan is currently closed for renovation. The alternatives were limited in Balakan so with the evening drawing in I decided to take my chances and head for the border and find somewhere in the Georgian town of Lagodekhi.

The first sign I was approaching the border was the tail end of a 3km long line of parked lorries. There is a tremendous amount of roadside litter along the road leading up to the border as well, not the most attractive corner of the country that’s for sure.

The beauty of a bicycle is you can easily glide past queues of lorries and see what the situation is at the front. The two Azeri soldiers checked my passport and gave me the knod. The Georgian soldiers took a little more time, but took pity on my disheveled appearance and showed me to the tap where I could freshen up. Within 30 minutes I was over the border and into Georgia.

———————-

A word on the people of Azerbaijan

I have never cycled through a country like Azerbaijan before. I don’t know if it is partly down to the absence of cycle tourists or foreign visitors in general, but I received the warmest welcomes I have ever experienced from strangers in the street. People would constantly wave from their cars or the side of the road, sometimes even pulling over to say hello and get a photo together. Thank you to everyone who welcomed and helped me on my journey through Azerbaijan, it was an experience I will never forget.

——————————

PHOTOGRAPHY: Azerbaijan

Leave a comment